Caleb Latas

Staff reporter

clatas@jccc.edu

The gray sketch paper was the size of a table for two, sprawled across his lap, he held the one-inch-long piece of graphite between his forefinger and thumb. His hands were smudged and calloused. Abstract blotches of shades of black colored the page, save for the white object of affection.

Across the fountain, her legs bent in a 45 degree angle, her back against the warm glossy-black stone. She was his muse. Dressed in pink and blue, she was now nothing but white space on the page. No longer an identity but the uncolored positive space. She was not important. What mattered was the space around; the negative.

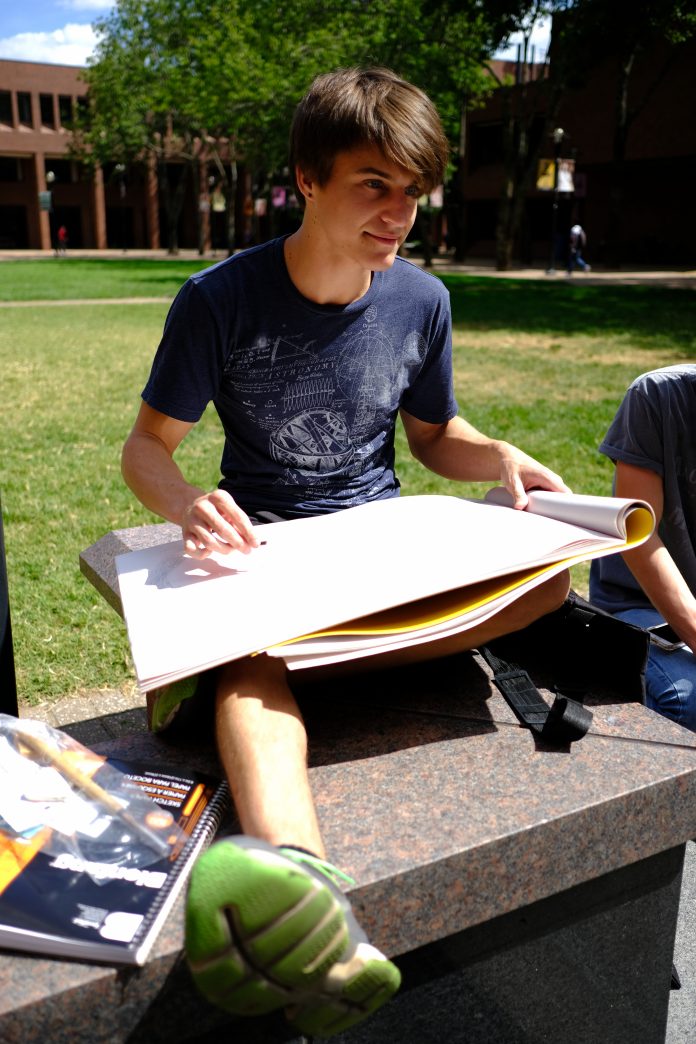

Caleb Hasenleder, attending his first semester at the college, sat on the raised wall along the sides of the fountain in the namesake square. The sun warmed the blackstone and helped fight off the cool breeze of the September day.

Sitting there, Hasenleder exudes a natural confidence and comfortability. He wears himself like a badge of honor. He carries scarred arms like medals of bravery and tenacity. True grit.

For Hasenleder the world is gray: dark gray, light gray, medium gray, gray-gray. It’s sometimes almost black, sometimes almost white, sometimes both. But never either or.

Hasenleder lives his life switching between the negative and positive dimensions and space. Like the physical girl, she is positive space, but on his sketch pad she becomes negative space. He turns her into emptiness and whiteness. She exist, but only in the space inbetween. Hasenleder turns this idea of negative and positive space on its head with the novel he is working on. He takes what is negative, what is space, what cannot be grasped, and turns it into the physical; the positive.

“[It’s about] something that is abstract coming into a physical plane,” said Hasenleder. “More specifically talks about someone who deals with greed or self consciousness or a mental disorder like borderline personality disorder or depression.”

For Hasenleder, the last part is personal. These intense feelings or anger, depression and anxiety become so strong they almost manifest themselves in physical form.

It’s this kind of spirituality that he finds himself enveloped in now. Though he has left the church, he maintains an agnostic ideology of the known and unknown, neither denying nor accepting a higher power.

Hasenleder left because he was no longer accepted, pushed and weeded out for his love and attraction. His sexuality. Because he loved a man, he was no longer allowed into the pearly gates.

Hasenleder didn’t want to be a part of any organization that would cast him out for who he was.

He didn’t want to be a part of the charade. Of accepting what is said, purely for the fact that it is said. Raised with blinders on, Hasenleder felt he was only allowed to look forward, not to question or see the world around him.

Leaving his previous life and the church has been like pulling out a weed for Hasenleder — he couldn’t just pull out the upper foliage of his upbringing; he had to dig his fingers deep into the dirt and rip it out, root and stem.

“I not only had to uproot my beliefs, but I had to uproot my experiences. The way I saw them — the way I would see my new ones.” said Hasenleder.

Having to find new ways to process the world around him, to deal with emotions and grief and suffering and existential crises, Hasenleder was like a newborn child now in the same world he had once known, but everything looked and felt different now.

Lucky for Hasenleder, he wasn’t alone. He had a support system outside of the church. In hindsight, he said, he would have left sooner. But this is an experience that had formed his being.

This has formed Hasenleder into the analytical observer he is now. He doesn’t feel, he processes. It’s the words he uses that signify this frame of mind. He spouts facts to justify, to source his idea. He speaks of neurons and neurotransmitters to explain his borderline personality disorder. He speaks of the gases that make the sky blue. He speaks of bones and flesh naturally and casually. He understands the world, and himself, not personally but rather informatively. He knows the chemical compositions of the matter around him.

Two sides of a coin, black and white, Hasenleder is artistic and scientific, he takes art classes and biology. Though those two are normally seen as separate, opposites, one black and one white, Hasenleder sees them as grey.