Five years ago today, the Van Allen Probes were launched into orbit to begin their study of the trapped radiation belts first predicted by and then discovered by Dr. James Van Allen with the first US satellite, Explorer 1. Fundamental Technologies in Lawrence, KS, where I do my space science research, is the Science Operations Center for the RBSPICE instruments on the two twin Van Allen Probes spacecraft. Through my work at FunTech, my wife and I had the honor and privilege of being invited to the Kennedy Space Center to witness our spacecraft leave the planet.

We were at Cocoa Beach for three nights where during the day we interacted with visitors to the Kennedy Space Center where we had a large display assembled sharing information about the mission, its objectives, and its importance to improving our understanding of space weather. As invited guests, we were given the opportunity to witness the launch from the same grandstands in which the families of the Apollo astronauts watched their husbands, brothers, and sons blast off on their epic voyage to the Moon. It was an awe-inspiring, thrilling, and ultimately frustrating experience.

We were at Cocoa Beach for three nights where during the day we interacted with visitors to the Kennedy Space Center where we had a large display assembled sharing information about the mission, its objectives, and its importance to improving our understanding of space weather. As invited guests, we were given the opportunity to witness the launch from the same grandstands in which the families of the Apollo astronauts watched their husbands, brothers, and sons blast off on their epic voyage to the Moon. It was an awe-inspiring, thrilling, and ultimately frustrating experience.

We had three nights and therefore three opportunities to get the Van Allen Probes off the planet, but on the first night, a launch was not even attempted. Engineers had discovered a flaw in one of the RD-180 engines in Huntsville, AL, the same type of engine that powered the Atlas V rocket underneath our spacecraft. The engines for our launch vehicle were inspected and found to be fine, so we were back on for night number two.

The launch window opened at 0430 which meant that we needed to arrive at Kennedy by 0030 to meet the shuttle busses that would take us to the viewing stands. Once at the viewing location, we had a magnificent view of our launch vehicle standing on its pad and illuminated by the brightest lights you can imagine. The atmosphere at the viewing site was thick with tension, anticipation, and mosquitoes. Lots of mosquitoes! During the long countdown, several speakers gave talks about the mission, which we all knew about already, and details about the launch sequence and timeline, which many of us did not know. What was truly special is that Maj. Gen. Charles Frank Bolden, Jr., Director of NASA, came out to address us and witness the launch with us.

The launch window opened at 0430 which meant that we needed to arrive at Kennedy by 0030 to meet the shuttle busses that would take us to the viewing stands. Once at the viewing location, we had a magnificent view of our launch vehicle standing on its pad and illuminated by the brightest lights you can imagine. The atmosphere at the viewing site was thick with tension, anticipation, and mosquitoes. Lots of mosquitoes! During the long countdown, several speakers gave talks about the mission, which we all knew about already, and details about the launch sequence and timeline, which many of us did not know. What was truly special is that Maj. Gen. Charles Frank Bolden, Jr., Director of NASA, came out to address us and witness the launch with us.

At 0400, we reached the T-4 minute hold. This was a preplanned hold during which final checks on the launch vehicle, the two Van Allen Probes spacecraft, and the launch conditions were made. Talk about tense and exciting! Movies always make the launch readiness poll sound over dramatic and you come away thinking, “Surely it’s not really that tense.” Yes it is; it really is. As each system was called out, the person responsible for that system would call out either “Go!” or “Go, Flight!” I get goosebumps even now just thinking about that moment.

At 0400, we reached the T-4 minute hold. This was a preplanned hold during which final checks on the launch vehicle, the two Van Allen Probes spacecraft, and the launch conditions were made. Talk about tense and exciting! Movies always make the launch readiness poll sound over dramatic and you come away thinking, “Surely it’s not really that tense.” Yes it is; it really is. As each system was called out, the person responsible for that system would call out either “Go!” or “Go, Flight!” I get goosebumps even now just thinking about that moment.

The Flight Director eventually got around to calling out, “Range.” The response was a pause, and then an utterly disheartening, “No go, Flight. No go.” That brought everything to an immediate halt. When there’s a range fault, it could mean that there’s someone in the restricted space in the air or ocean that’s fouling the range, or it’s an instrumentation failure. Many of our thoughts in the grandstands was that if it were a bunch of boaters out where they shouldn’t be, there might be violence done that day. As it turned out, it was the fault of a transponder on the launch vehicle that couldn’t maintain a frequency lock on the downrange radar.

All launch vehicles are actively tracked. A radar site doesn’t simply passively track them, they actively communicate with the launch vehicle to monitor the rocket’s attitude and trajectory with great precision. The reason for this is that if a rocket begins to stray from its designated trajectory and begin headed inland where it may fall on a populated area, the vehicle will be destroyed instantly. The last thing NASA wants is for a US missile to land and explode in a US city.

So with no launch on the second night, we all went back to our hotel rooms, caught what sleep we could before going back to the Visitor’s Center and our booth to do more public outreach in the afternoon. That night, we all got up again and went back to Kennedy at 0030 to give the launch one more try. Again with the speeches. Again with the explanations. Again with the waiting, the tension, the anticipation, and swarms of mosquitoes. Once again, we reached the T-4 minute hold. Once again, we listened nervously to the launch readiness poll.

“Hydraulics.”

“Go!”

“Water.”

“Go!”

“Range.”

And after a long pause, “Go, Flight!”

There was an uproar of cheers! It was as our team had just won the World Series! Everyone was jumping, clapping, and cheering, but the poll wasn’t over yet.

“Weather.”

“…No go, Flight. Weather is no go.”

It was a soul-crushing moment. All the anticipation, all the excitement was dissipated in an instant. The weight of all of the work that had gone into making the Van Allen Probes, its array of instruments, and all of the software to control the spacecraft and their instruments crashed down upon us. For many of us, myself included, this was our first time, perhaps the singular time in our lifetimes, of getting to witness a rocket launch, and certainly the singular time we would be able to watch from such a historically significant location. There were tears. I’m not ashamed to admit it.

My wife and I along with my fellow colleagues flew home. There was still work that needed to be done on other missions, and the Fall semester had started, so I had to get back to the classroom. It wasn’t a fun trip back, and I moped around campus that Monday. The Van Allen Probes obviously did launch successfully, but not until the Thursday of the week after we were there. My newborn daughter and I were up at 0300 to watch the launch on NASA TV, and again I wept. This time happy to see our spacecraft finally on their way during a flawless launch.

Five years later, the two spacecraft are still going strong and providing truly unique perspectives and data on the working of the Earth’s trapped radiation belts, the ring current, and space weather in general. We’re still the Science Operations Center for RBSPICE, and we’re still finding out new things about our near-Earth space environment. It’s been a great five years, and here’s hoping for at least a couple more.

You can learn more about the Van Allen Probes mission and the RBSPICE instrument by following the links below:

http://vanallenprobes.jhuapl.edu/

http://rbspice.ftecs.com/

You can see my gallery of photos from our time down at the Kennedy Space Center and Cocoa Beach here:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/xorpheous/albums/72157631262396530

We were at Cocoa Beach for three nights where during the day we interacted with visitors to the Kennedy Space Center where we had a large display assembled sharing information about the mission, its objectives, and its importance to improving our understanding of space weather. As invited guests, we were given the opportunity to witness the launch from the same grandstands in which the families of the Apollo astronauts watched their husbands, brothers, and sons blast off on their epic voyage to the Moon. It was an awe-inspiring, thrilling, and ultimately frustrating experience.

We were at Cocoa Beach for three nights where during the day we interacted with visitors to the Kennedy Space Center where we had a large display assembled sharing information about the mission, its objectives, and its importance to improving our understanding of space weather. As invited guests, we were given the opportunity to witness the launch from the same grandstands in which the families of the Apollo astronauts watched their husbands, brothers, and sons blast off on their epic voyage to the Moon. It was an awe-inspiring, thrilling, and ultimately frustrating experience. The launch window opened at 0430 which meant that we needed to arrive at Kennedy by 0030 to meet the shuttle busses that would take us to the viewing stands. Once at the viewing location, we had a magnificent view of our launch vehicle standing on its pad and illuminated by the brightest lights you can imagine. The atmosphere at the viewing site was thick with tension, anticipation, and mosquitoes. Lots of mosquitoes! During the long countdown, several speakers gave talks about the mission, which we all knew about already, and details about the launch sequence and timeline, which many of us did not know. What was truly special is that Maj. Gen. Charles Frank Bolden, Jr., Director of NASA, came out to address us and witness the launch with us.

The launch window opened at 0430 which meant that we needed to arrive at Kennedy by 0030 to meet the shuttle busses that would take us to the viewing stands. Once at the viewing location, we had a magnificent view of our launch vehicle standing on its pad and illuminated by the brightest lights you can imagine. The atmosphere at the viewing site was thick with tension, anticipation, and mosquitoes. Lots of mosquitoes! During the long countdown, several speakers gave talks about the mission, which we all knew about already, and details about the launch sequence and timeline, which many of us did not know. What was truly special is that Maj. Gen. Charles Frank Bolden, Jr., Director of NASA, came out to address us and witness the launch with us. At 0400, we reached the T-4 minute hold. This was a preplanned hold during which final checks on the launch vehicle, the two Van Allen Probes spacecraft, and the launch conditions were made. Talk about tense and exciting! Movies always make the launch readiness poll sound over dramatic and you come away thinking, “Surely it’s not really that tense.” Yes it is; it really is. As each system was called out, the person responsible for that system would call out either “Go!” or “Go, Flight!” I get goosebumps even now just thinking about that moment.

At 0400, we reached the T-4 minute hold. This was a preplanned hold during which final checks on the launch vehicle, the two Van Allen Probes spacecraft, and the launch conditions were made. Talk about tense and exciting! Movies always make the launch readiness poll sound over dramatic and you come away thinking, “Surely it’s not really that tense.” Yes it is; it really is. As each system was called out, the person responsible for that system would call out either “Go!” or “Go, Flight!” I get goosebumps even now just thinking about that moment.

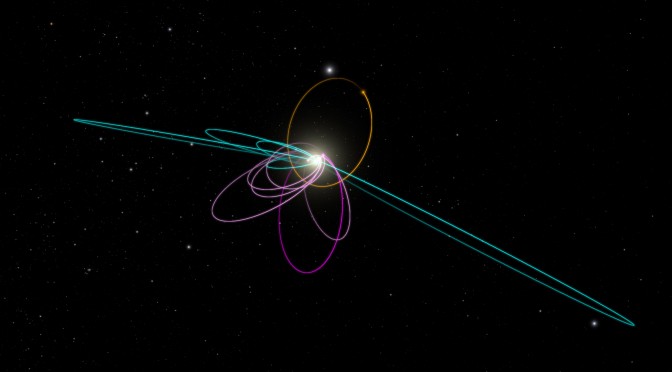

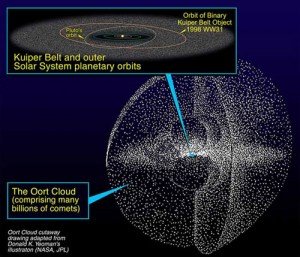

This places its perihelion around 280 AU. That’s really far out there, and places the proposed object as a member of the distant Kuiper Belt or inner Oort Cloud, or Hills Cloud, rather than a member of the inner Kuiper Belt wherein resides more familiar objects like Pluto and Eris. The mathematics are extremely compelling and the discussion and conclusions well-reasoned, but as the modern saying goes, “Pics or it didn’t happen.”

This places its perihelion around 280 AU. That’s really far out there, and places the proposed object as a member of the distant Kuiper Belt or inner Oort Cloud, or Hills Cloud, rather than a member of the inner Kuiper Belt wherein resides more familiar objects like Pluto and Eris. The mathematics are extremely compelling and the discussion and conclusions well-reasoned, but as the modern saying goes, “Pics or it didn’t happen.”