Cookbook Reviews by Andrea Broomfield

This series is purely my indulgence. I admit to an obsession with British cookbooks and cuisine and would like to share my thoughts from time to time with other Anglophiles interested in current culinary trends. So what are current UK culinary trends and what recipes are worth trying at home?

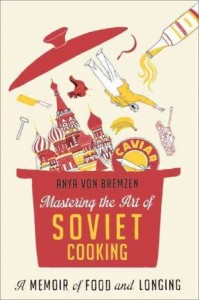

• Andrea’s Cookbook Review #7: Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking: An Unexpectedly Rich Food Memoir about a Nation by Anya Von Bremzen

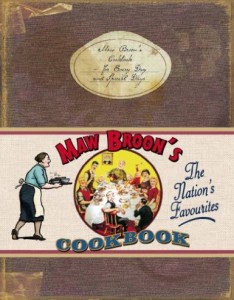

• Andrea’s Cookbook Review #6: Guid Scottish Cooking: Maw Broon’s Cookbook: The Broon’s Cookbook– for Every Day and Special Days

Lovers of Scotland will immediately recognize that Maw Broon and her family—Paw Broon (Maw’s husband), Granpaw Broon, Hen (Henry), Daphne, Joe, Maggie, Horace, the Twins and the Bairn— as in the famous Broons of a comic strip that has appeared in the Scottish Sunday Post since the 1930s. Those who do not know Scotland but who are interested in Scottish culture must read up on the Broons, which is the Scottish dialect word for Browns, as in the Brown Family.

Several Maw Broon cookbooks are out there, but Maw Broon’s Cookbook for Every Day and Special Days is my all-time favorite. I was introduced to the Broons and their cookery by a friend of mine who helped me a couple of years ago write an article on Scottish cuisine.

The cookbook is designed to look like a family scrapbook of recipes, complete with grease spills, hot tea rings, and various annotations put in their by the Twins (who are young) and by Maw and Paw’s adult children who like to add their comments on their favorite dishes.

“Stapled” to some of the pages are various Broon comic strips that give readers unfamiliar with the Broons a sample of why they are so beloved in Scotland.

The cookbook rests on the fiction that when Maw married Paw, Maw’s mother-in-law presented to her her own favorite recipes as well as instructions on how to cook them. She writes, “Dear Maggie, Welcome tae the family. This book is a collection o’ recipes that my ain mither passed tae me, an’ there’s bits an pieces that have come my way from freens and neebours over the years. It’s food fur week days, high days an’ holidays. Ye’ll find a’ the recipes that your man is familiar wi’ in here.

This cook book was actually published in 2007 but truly has the feel of being timeless, and because it is designed to include the various newspaper recipes and cookery cards that Maw’s mother-in-law has pulled out and stapled in, one really does get the feel that they are reading a family heirloom, chock-full of all sorts of helpful hints and recipes from the newspaper and from family friends.

The manuscript font also adds to its sense of authenticity. Nothing is in print except for the various newspaper clippings; the rest is in Jeannie Broon’s lovely scrip (Jeanie being Maw Broon’s mother –in-law).

The cookbook is proudly Scottish, and in this sense, it goes some distance in helping readers see the similarities as well as the distinct differences between Scottish and English culinary traditions. In Maw Broon’s book for example, you will find recipes for what we might think of as Scottish national dishes: porridge, oatcakes, mince and tatties, stovies, bannocks, Cullen skink, Scotch Broth, cock-a-leekie (complete with the prunes), feather fowlie, Hogmanay steak pie, leek pie, and skirlie, among so many others. Rather than translate all of these dishes into plain English, I encourage readers to order this wonderful cookbook and get lost in Scottish culinary culture.

Given Scotland’s proximity to England and its relationship with that country, many dishes in Maw Broon’s Cookbook are also English and make a wonderful addition to any Anglophile’s collection. Reliable recipes for classics such as bacon and egg pie, potato croquettes, custard sauce, and gooseberry trifle are among my personal favorites.

Also check out:

Maw Broon’s But an’ Ben Cookbook

Maw Broon’s Kitchen Notebook

Maw Broon’s Afternoon Tea Book

The Broons’ Burns Night (one of my all-time favorites as well!)

Andrea Broomfield, Ph.D.

Professor of English

abroomfi@jccc.edu

http://andreabroomfield.blogspot.com/

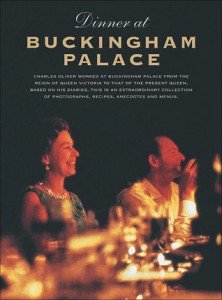

• Andrea Broomfield: Review #5 (February 18, 2013)

Anyone for Dinner with the Queen? Read on, and See. . . .

Dinner at Buckingham Palace by Charles Oliver. Edited and compiled by Paul Fishman and Fiorella Busoni (1007)

I have not made anything from Charles Oliver’s Dinner at Buckingham Palace. Many recipes are overwhelmingly fussy, and even if they are not fussy, the ingredients are either too expensive or too difficult to obtain: consommé with fumet of duck, leverets, and fresh turtles, truffles, and other such ingredients appear frequently. Of course, that’s part of what it means to eat like a royal, so the cost, scarcity of ingredients, and fuss are in order. However, what I do find surprising is how boring so many of the recipes are! Take as an example Chicken Panada, where a perfectly acceptable young fowl is roasted, but then its white meat is pounded with bread crumbs soaked in broth, then diluted with a bit more broth. The whole mess is then pushed through a tammy (or food mill), and served “moderately warmed in custard cups.” Although listed in among such delights as Ceylon Moss Gelatinous Chicken Broth and Macaroni Soup a la Royale, Chicken Panada belongs in the sick room of a Victorian mansion (and woe to the poor invalid stuck with it).

Which perhaps brings us to the point of this particular cookbook: it is a treasure trove of recipes that indicate how little British Royal tastes have apparently changed, and as such, it is an essential scholarly reference work for a British food historian.

So here, then, are some of my scholarly musings.

Charles Oliver was the son of a royal servant and who likewise became a servant, working for the royal household all of his life, except during World War One. Those familiar with Downton Abbey, or Remains of the Day will likely understand such loyalty to one’s lord and Queen. Young Charlie’s passion was food, and although his injuries from the Great War never allowed him to become a royal chef, he nonetheless spent time in the kitchens and kept detailed notes on what was prepared. After many years, he amassed a collection of recipes and menus, as well as various anecdotes that related to the workings of the kitchen and the Royals at their meals. He wished that after his death, his material be compiled into what he described as “a cookbook with a difference” (xiv). Oliver died in 1965, and half a century later, his wish came true.

The cookbook’s editors have fleshed out Charles Oliver’s memories and have brought the book up-to-date by offering some insight into what Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip enjoy eating at home. It is stunning to me how the food that was prepared for Victoria, Edward VII, George V, and so on, still remains appetizing to Elizabeth II. As a Defender of the Faith, I am guessing that the monarch might ultimately be more useful (or useless, depending on your viewpoint) as Defender of the British Diet.

Prince Charles is right in there with his mum, playing an active role in calling attention to British farmer’s markets, artisan cheeses, and what remains of the British countryside. It appears that these inclinations were with him as a boy, where he learned to fish and hunt, but also to garden and act as steward for the thousands of acres of royal forests, gardens, and orchards. A photo of Prince Charles as a young man standing at a Cambridge farmer’s market, intently listening as two farmers describe their wares, is one of my favorite photos in this cookbook.

But in traditional British fashion, the vegetables that appear on the Royal dinner tables are not very interesting when it comes to preparation. Take Choux de Bruxells ( i.e., Brussels sprouts): trim away bruised or discolored leaves, boil them for ten minutes briskly until tender. That’s it—the whole “recipe.” Or, what about Petits Pois au Beurre (i.e., peas with butter)? Cook the peas until tender, drain and toss them over a fierce heat to dry, add a pinch of powdered sugar and then toss with butter. I acknowledge that what makes such a recipe extraordinary is that the peas are garden fresh, and unless one has a garden, getting fresh peas is very difficult. They lose their flavor after only a few hours once they are out of the pod, so the idea of having gardeners to pick and shell one’s peas the afternoon one requires them for dinner is worth envying.

Also in the traditional British fashion, French names are applied to the most pedestrian of fare—as we see above with Choux de Bruxelles. Several recipes in the meat chapter testify to this trend as well. Take Cotelettes d’Agneau sur le Grille, or grilled lamb cutlets. Trim the cutlets of gristle and superfluous fat, dust with salt and pepper, lightly brush with olive oil and grill. Okay, but why the French name? What’s wrong with Grilled Lamb Cutlets? Also intriguing to me is Carre d’Agneau Sauce Menthe, or roast lamb with mint sauce, a perennially favorite British meal. In fact, many British people cannot think of any herb other than mint to serve with lamb, and this has been the case for at least a couple of centuries. I do not think the French are as keenly devoted to lamb and mint sauce as the British, so why give this dish a French name? Furthermore, the technique for making the mint sauce is unimaginative (alas, British) at best: take two tablespoons of chopped mint, add to it one tablespoon of sugar, one tablespoon of boiling water, and 1 ½ tablespoons of vinegar. Mix it up. Serve with lamb.

I do not wish to imply that I dislike British food. I absolutely love the best that this tiny island nation with its extraordinary infusion of Colonial tastes has to offer. Succulent roast beef with heaping mounds of grated horseradish, a lovely roast chicken with sage stuffing, a platter of shepard’s pie, with the mashed potatoes pooling with melted butter: these dishes are ones that I crave and which make me wish every day to return to the UK. However, the British are not renowned for their culinary skills or at least until recently, their adventurous palates, and the recipes reflect that reality.

More problematic, and more likely the result of Charles Oliver not being a cook himself than any other reason, are the number of very poorly conceived recipes in this cookbook. If readers actually purchase Dinner at Buckingham Palace with the intention of using it for something more complicated than Cotelettes d’Agneau sur le Grille, they should be competent in the kitchen, or food poisoning might be the result.

Take as an example Oliver’s various recipes for chicken. He advises his readers that they can roast a three-pound chicken in 25 minutes! I could just see some novice trying that and cutting into a chicken that was still literally raw. And eating it anyway! After all, the recipe is published, and it comes from the Queen’s own recipe archivist. How could it be wrong? These kinds of errors in method are distressingly common throughout the book, and again, I think that because of them, Dinner at Buckingham Palace is more about a culture, about a way of life, about the continuity of culinary tradition, than it is about actual recipes.

The Royal Family at Breakfast, 1965

Courtesy of The Independent http://www.independent.co.uk/incoming/article7811699.ece/ALTERNATES/w460/5404088.jpg

For readers interested in Royal food facts, check out this wonderful article from the Independent: http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/food-and-drink/features/exclusive-insiders-guide-60-royal-foodie-facts-for-60-years-of-hrh-7804796.html

And, on a more light-hearted note, I urge readers to check out the series of super-funny satires on aristocratic cooking, Posh Nosh. Start with Episode One and watch them in order. You will find them droll, and a very smart analysis of food and class in Britain. They are available on YouTube and each one lasts approximately nine minutes: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bzjR0yL4f0Y

• Andrea Broomfield: Review #4 (January 22, 2013)

A Brit’s Take on American Food: Jamie Oliver’s America (2009)

I love Jamie Oliver. I have several of his cookbooks and turn to them when I demand British comfort food, particularly toad in a hole, chicken and mushroom pie, chicken tikka masala (the most popular dish in Britain, by the way), and my kids’ hands-down favorite, roly poly, where pie crust is rolled out, topped with treacle, golden syrup or jam, rolled up, and baked until golden. When it comes to Jamie’s interpretation of such classics, he is in his zone. The recipes are beautifully conceived, updated to accommodate modern tastes, not overly difficult to make, and delicious. Read more of the review . . .

It was with interest, then, that I read and cooked from Jamie’s America: Easy Twists on American Classics, and More. I was curious to see how a Brit would he interpret such classics as apple pie, fried chicken, and corn on the cob—or would he?

Jamie’s method certainly made sense. He recognized that as the husband of a (then) pregnant wife and two young kids, he could not do exhaustive travel, so he pinpointed six places to “kick-start [his] voyage of discovery.” They included New York City and Los Angeles. He travelled to Louisiana because of its amazing cultural mix. The South fascinated Jamie, so he moved on to Georgia with its soul food and barbeque. From there, he journeyed to Arizona because “to properly get to grips with American food,” Jamie needed “get back to the original landlords of the country: the Native Americans.” Due to his interest in cowboys, Jamie concluded with Wyoming.

So, does Jamie “get it”? Are his recipes authentically American? There’s no way anyone could answer that, not even Americans! As Jamie points out, the “U.S. is built on wave upon wave of immigration,” and as such, American food is not bound up in one cooking tradition the way so many other parts of the world are. That fact makes American cuisine “really interesting . . . from a food perspective,” Jamie (and I) conclude. So, I admit that I am not an authority on authentic American cuisine. I just know what tastes good, and I have a basic, academic and practical understanding of the ethnic traditions make American cuisine extraordinary. Sometimes with Jamie’s cookbook, I think he is more interested in interpreting American classics for a timid Brit audience when it comes to the bold flavors that define our food, or I think that because he’s a Brit, he doesn’t always get it right. But you will have to locate the book and be the judge of that. There are just my thoughts.

In terms of the spirit of his endeavor, Jamie has a lot of success. He befriends people whose kitchens, restaurants, churches, BBQ shacks, campfires, and food trucks inspire him. He learned from those people, who taught him techniques that all Americans who love food should know: how to prepare gumbo, make matzo balls, pizza crust, Navajo flatbreads, and pie. Americans who respect great food and tradition will appreciate Jamie’s recipes for these techniques.

Jamie is also whimsical and ambitious—the characteristics that define all of his cookbooks. He can take native ingredients like watermelons, tomatoes, and chilies and create delicious, imaginative recipes that showcase American flavors. I have never had a watermelon salad in the UK, but thanks to Jamie’s take on a watermelon salad, my guess is that he will introduce Brits to flavor combinations that spark their taste buds as much as ours. He starts with icy cold melon and mixes it gently with pumpkin seeds, sunflower seeds, chili powder, sheep’s cheese (like feta), chopped mint and scallions, lime juice, and a Scotch bonnet pepper for added heat. The composition is not traditionally Navaho, (his inspiration) but the foodstuffs are.

Sometimes, though, Jamie’s Britishness gets in his way; he takes American dishes that I hold dear and. . . . messes them up (literally).

Brits love an Eaton Mess—a compilation of meringue, fruit, and cream that figures largely in that nation’s culinary history. Jamie’s “My NYC Cheesecake” is just plain wrong to me because he attempts to transpose Eaton Mess right onto the cheesecake. Everything is fine with his cheesecake until he adds that meringue topping. Meringue topping!? To a New York cheesecake? Please! Maybe it would be bit better if the meringue stayed soft (like on top of a lemon meringue pie), but he wants it hard and crunchy, and that’s just not right, not if you are a purist when it comes to NY cheesecake, at any rate. YUJK.

Then there’s the problem with barbeque: Who could blame Jamie for being enamored with barbeque? Most Americans are born with an innate understanding and a worship of barbeque. Take the amazing essay by one of my favorite food authors, Wright Thompson, “Memphis in May: Pork-a-Palooza,”

(http://gardenandgun.com/article/pork-palooza) where he totally gets that for Americans, barbeque is religion, right up there with redemption and sacrifice! From Kansas City, to Memphis, Little Rock to Dallas, then the whole of North Carolina and Georgia, barbeque is quintessential American food. But most of Jamie’s recipes for American barbeque, use an oven. God forbid. An oven?! That’s just not right, in my book. Where’s the smoker? Or at the very least, the Weber? While sometimes Jamie will give an alternate recipe for using an outdoor grill, he shies away from a smoker in all cases and seems in love with a boring old oven. I associate ovens with “funeral meat,” the massive amounts of cheap beef or pork that have to be cooked in a disposable tin-foil tub, in a church basement utility oven, to feed the hundreds of bereaved who wonder down from the sanctuary into the church basement to confront that funeral supper. Please, do not commit such an injustice to my corpse. The idea of a florescent-lighted, dingy church basement and loads of cheap funeral meat will turn me into a ghost who haunts you in agony until your own demise! Oven-roasted meat in my book is not barbeque, and I just do not trust Jamie’s attempts to translate the pit-smoked ribs that he ate with abandon on his trip through Georgia, and even New York, into something authentically American if he’s using an oven.

Then there’s chili. “Chili Con Jamie” does not get me excited. Brits just cannot seem to get away from serving chili with rice, for one thing! I can’t count the number of pubs I have visited in the UK where inevitably there’s Chili Con Carne on the menu, dumped over white rice. Now, I think that beans and rice—as in red beans and rice, or pinto beans and rice—make sense. I like beans and rice. But there’s just something not right to me about taking a great American classic like chili and dumping it over rice. Even worse, Jamie suggests you might want to serve his chili with potatoes instead of rice. Making the situation even worse, Jamie also suggests using butter beans—lima beans, basically—in the chili, and that just is not even worth considering! Not in my family, at least.

Jamie is creative and bold, and he has a talent for taking American foodstuffs and offering tasty interpretations. He canvasses a huge country and goes some lengths to disprove the conventional wisdom that American food is junk food. Furthermore, he inspires British cooks and American cooks to try some excellent dishes– and if they can’t get alligator or crawfish to make them, then at least he inspires them to to dream. But if you want a terrific American cookbook, then look at the compilations put together by Cook’s Country, or my very favorite, the massive One Big Table by the incomparable Molly O’Neill. Jamie’s take on American food is just slightly off kilter, and people who champion great American cuisine should be aware of that when they buy or check out this cookbook.

By the way, when I was in London this past October, I saw Jamie’s America on display all over Britain’s biggest bookstore chain, Waterstones. At its Bloomsbury branch, close to my hotel, I was fascinated to see that it was a best seller; I was actually gratified to see a lot of Londoners browsing the book and then purchasing it, because it meant that Jamie had piqued their interest in food on our side of the pond. Even if I took issue with some of Jamie’s interpretations of classic American foods, my guess is that he at least made many American dishes sound appealing to his British audience, and that is a start.

Some of my favorite recipes from Jaime’s America include

Waldorf Salad My Way

Fiery Dan Dan Noodles (I make it all the time.)

NYC Vodka Arrabbiata (I make it all the time.)

Beautiful Breakfast Tortillas

Mexican Breakfast (I make it all the time.)

• Andrea Broomfield: Review #3 (December 10, 2012)

Eating for England: The Delights and Eccentricities of the British At Table by Nigel Slater (2008)

I loved chef Nigel Slater’s Toast: The Story of a Boy’s Hunger, his funny and poignant memoir of growing up in Post-World-War-II Britain, and I very much enjoyed Eating for England, a collection of short essays on all matters related to English food. Buried towards the end, I found a particularly memorable essay, “The Cool, Modern Shopper Cook,” and I think it best sums up what Slater most wishes for his country’s attitudes towards food to become, as well as what he personally strives for gastronomically. If you don’t know Slater, you might really enjoy some of his cookbooks, too, including Real Food.

Some of the essays (paragraphs, really) in Eating for England, are funny and droll, for example, “Things Move On,” which points out how much easier life was when one simply needed a bowl of hot water and a squeeze of Fairy Liquid to do the dishes, as opposed to nowadays needing a “machine, dishwater tablets, rinse aid, dishwasher salt, a maintenance contract and something called a dishwasher cleaner.” Others are full of nostalgia for foods that no longer exist in England, but that nonetheless bring back wonderful memories.

The shortness of the essays made this book perfect for moments when I found myself waiting and did not have the ability to devote time to sustained reading. I also found it particularly fun to read while on the treadmill, where my concentration is not at its best, but I am in need of something to take my mind off the fact that my intervals are getting harder and longer! Wanting to continue to read Slater’s book helped motivate me to keep moving! I also appreciate the humor of reading about food while working out!

The book’s organization is a bit perplexing, and so many short essays seem to belong in a unit, rather than being scattered about, slapped down (it appears) whenever Slater thinks of a topic again, or has more to say on the same topic. Toast, crumpets, high teas, muffins come up a lot, and his thoughts about them are sometimes repetitive. That’s really a minor complaint, though, because sometimes I liked being reminded of what I had already read–it gave me more to think about than otherwise, perhaps.

If you enjoy this book, then you will be anxious to take another trip to Brits in Lawrence and notice all the various items for sale there that you likely overlooked!

• Review #2: (November 12, 2012)

Nigella Lawson’s How to be a Domestic Goddess: Baking and the Art of Comfort Cooking. London: Chatto & Windus, 2000

Now That’s British!

Nigella Express (see previous post) is fairly insignificant in the Lawson cookery canon. After all, celebrity British cookbook authors such as Nigel Slater, Jamie Oliver, and most certainly NigellaLawson, are expected to trot out some sort of “express cookery book” after they have made a huge splash with a serious tome—those cookbooks that maintain Britain’s respectable status on the world culinary stage. While Lawson’s How to Eat established her popularity back in 1998, it was her second book, How to Be a Domestic Goddess: Baking and the Art of Comfort Cooking, that catapulted her to fame when it was published in 2000. As a result, Lawson was deemed Author of the Year at the British Book Awards in 2001. I like Nigella Express, but I treasure How to be a Domestic Goddess because it’s important to British culinary history and helps me understand current, important conversations about British cooks and cooking. . . . to see the full review click here.

While Domestic Goddess includes recipes that are American (Boston Cream Pie, Snickerdoodles, Brownies, Snickers and Peanut-Butter Muffins), and Continental European ( Certosino, Pizzza Casareccia, Apple Kuchen), its strength lies in its authoritative, yet imaginative approach to British iconic dishes: steak and kidney pudding, Christmas cake, mince pies, Cornish pasties, scones, and a host of other such delights.

Lawson is at her most talented, at her most confident, when she sticks to British cuisine. True, some of her non-British recipes are absolutely lovely—Pizza Rustica is amazing, for example—but many are border-line unappetizing or odd, at least to me. Her British take on that wonderful New England summertime staple, Blueberry Boy-Bait , is to top it with crunchy meringue. No! That’s just wrong, I would argue. Her recipe for Snickerdoodles does not call for the essential Cream of Tartar, and because the measurements are just slightly not right by American standards, the cookies do not spread properly, and they lack that oh-so-subtle tang that comes from a Snickerdoodle done right. If you want these recipes or ones for banana bread and chocolate chip cookies, I urge you to stay with American authorities on such matters

But Lawson’s lemon syrup loaf cake? There simply is no better recipe than this one. Her Madeira cake? Heavenly in its very plainness, its championing of the most simple ingredients. Take her advice and add the caraway seeds, and I promise that you will be transported to Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford village at tea-time.

More important to me is the cultural context of Lawson’s cookbook. She is engaged in an ongoing debate with Delia Smith, who might best be understood as Britain’s modern version of the formidable Isabella Beeton. Matronly and Victorian with her no-nonsense, extremely correct, and scientific approach to cooking, Delia Smith has managed to make some Brits feel guilty and bad about themselves, given their slovenly, lazy culinary habits. Smith is notorious for having angered readers for her patronizing instructions on how to boil an egg. Smith’s series, How to Cook, is formidable and important, but Smith not sexy, and she’s not young, and she’s a reminder of the nightmare days of girls’ Domestic Science classes in high school. Smith insists on being serviceable, and she refuses to cater to Brits’ love of using food shows as pure entertainment while they eat their Sainsbury ready meals or dump their tins of beans on toast. Delia Smith seriously wants average Britons to learn how to cook, and they refuse because just like children, they resist what they jolly well know is good for them.

The title of Nigella Lawson’s first big splash is a direct repudiation of Delia Smith’s approach to food. While Smith insists on teaching her recalcitrant charges How to Cook, Nigella Smith gleefully and impudently insists that they instead learn How to Eat. How to Be A Domestic Goddess continues Lawson’s gleeful impudence. As she rather snipingly points out in her Preface, her book is not about baking—“not in the sense of being a manual or a comprehensive guide or a map of a land you do not inhabit.” It is not “skin-of-the-teeth efficiency, all briskness and little pleasure” like Delia Smith’s books; rather, Lawson explains, it is about tempting reluctant, scared, ego-wounded Brits to return to the “familial warmth of the kitchen we fondly imagine used to exist.”

I admit that Delia Smith is too basic for me. She’s like Betty Crocker. However, were I just starting out and timid in the kitchen, I would yearn for Smith’s matronly authority and comfort as I practiced boiling rice and scrambling eggs. She will be the reassuring guide my daughter will need when she heads to college next year. Lawson, on the other hand, is aimed (no matter how Lawson would protest) for the person who is comfortable making pie crust and gin and tonic jellies. She is edgy, she is talented, and she is an artist, especially when it comes to recipes for new interpretations of British classics. If you have any command of a kitchen, then I highly recommend How to Be a Domestic Goddess.

My favorites:

Lemon-Syrup Loaf Cake

My Mother-in-Law’s Madeira Cake

Victoria Sponge

Irish Blue Biscuits

Oatcakes

Lily’s Scones

Cornish Pasties

Cheese, Onion and Potato Pies

Rhubarb Tart

Gin and Tonic Jelly

Trifle

Store-Cupboard Chocolate-Orange Cake

Fresh Gingerbread with Lemon Icing

Christmas Cake

Boxing Day Egg-and-Bacon Pie

• Review #1: (October 17, 2012)

Nigella Express: 130 Recipes for Good Food, Fast (2007)

I’ll start with Nigella Express: 130 Recipes for Good Food, Fast (2007) just because it’s handy.

I love the revealing photograph on the cookbook’s end sheets. We are allowed a full-frontal view of what is presumed to be Nigella’s over-stuffed pantry, with all the items nonetheless neatly arranged, stack upon stack, row upon row.

And what is revealed? Of course, Nigella wants us to see how much she relies on that stocked pantry to whip up a meal in thirty minutes, but the cultural anthropologist sees more.

“The British kitchen,” Nigella’s pantry triumphantly proclaims, is truly, unapologetically, international!” Gone are the days of monotony, of stodgy, steamed Spotted Dicks, grey minced mutton atop watery boiled potatoes, and treacle puddings congealing in their own fat. Gone are those fusspots and cranks who peevishly denigrate all things French, particularly those horrid French “messes” (i.e, rich ragouts, succulent braised beef, salmis of duckling, and fricandeaus of turtle), and gone too are the formidable nannies who insist that their charges not be allowed both butter and jam on the bread, but one or the other—else the sin of gluttony be instilled and compromise the moral integrity of the Empire’s future leaders.

It’s not that puddings and treacle tarts and rhubarb fools and steak-and-kidney pies are entirely gone from the British culinary lexicon, Nigella implies in the various pages of her cookbook, but now, thanks to globalization and the British (Culinary) Enlightenment, those staples can exist alongside a host of international dishes—all made effortlessly, thanks to the thousands of international shortcut products available in groceries and via mail order.

The row in Nigella’s pantry that stands out in the photograph starts with a bottle of chili oil with Asian characters on the label, thus indicating that Nigella’s willingness to venture into obscure, likely cramped and shadowy Asian groceries for authentic goods at rock-bottom prices. But if chili oil is a thrifty purchase, Nigella’s sack of Guiseppe Cocco sitting next to the chili oil suggests that Nigella is also happy to indulge in splurges at upscale Italian import stores in tony Mayfair (or a similar distrct), or perhaps at her nearest Waitrose (http://www.waitrose.com/) a full-scale grocery store that crosses Dean and DeLuca with Whole Foods and Zabar’s.

In other words, it’s not thrift that drives Nigella’s cooking, so much as a desire to be cosmopolitan and adventurous in her tastes, to save money if it’s convenient, and to spend lavishly if the product is high quality and will go some way in making a throw together dessert like her Totally Chocolate Chocolate Chip Cookies taste great.

Alongside the sack of Guiseppe Cocco sits what to Americans seems downright pedestrian and ho-hum: Mott’s Original Apple Sauce. Some American processed foods, Nigella’s pantry seems to suggest, are actually icons of good taste in the UK. On our side of the Atlantic, some might equate Cadbury’s chocolate or Carr’s biscuits with good taste for similar reasons. Next comes another Asian import, mustard greens, and they nestle next to a tiny jar of Colman’s Mustard. Working as a sort of backdrop to the tinned Asian greens and Coleman’s is a huge box of PG Tips tea. Moving on, we see a spice tin of Santo Domingo Sweet-Smoked Pimenton de La Vera, (although for me to tell you that with authority took some time with a magnifying glass and with Google Images). Nigella clearly loves cocoa powder, because stuffed behind that tin of Santo Domingo Pimenton is yet another sack of the Guiseppe Cocco. “It happens all the time, doesn’t it.”, we hear Nigella speaking to us. “We think we’re out, so we buy more, only to find a half-used sack hiding behind the jar of Opies Baby Pears with Vanilla!”

Towering like Pisa next to that second sack of Guisepe Cocco is another American name-brand icon, Nestle Toll House Swirls. To keep the leaning tower of Toll House Swirls from falling over, is a bottle of Nolans Road Extra Virgin Olive oil from South Australia. And finally, finishing out the row is the third American icon in one row: Skippy Peanut Butter, shoved right up against Wing Yip Hoisin Sauce.

Now, what’s going on here? One can see Nigella’s pride in her tastes and in her free-wheeling spirit. She searches everywhere, in Darkest London and Harrod’s Food Hall, for the best ready-made foods and flavors. The bolder, the more exotic, the better, but nonetheless, when she wants comfort, there’s got to be the soothing British standbys as well.

I can see Nigella traipsing home from one of her many photo shoots on a rainy, foggy day in London Town. She’s thinking, “I need a nice cuppa and a toasted crumpet,” and like thousands of well-heeled Brits, there’s only a couple of brands that suffice in just such a situation: PG Tips and Wilkin & Son’s Red Currant Jelly (or one of their other luscious flavors, like orange marmalade and malt whiskey, or its lemon curd. http://tiptree.com/goto.php?sess=+A5E514719+F56+F18435A52&id=2

Just like in the USA it has to be PB&J I with Skippy for a comfort food feast on a rainy day, in England, it had better be PG Tips and Wilkin & Son jam for tea. I’m totally okay with that, by the way. I love both. I find PG Tips for dirt cheap at Indian groceries here in Overland Park, Kansas just like Nigella finds her chili oil and of Asian greens in similar locales (I’m guessing). And, I always stock up on Wilkin & Sons conserves, marmalades and curds when I head to Brits in Lawrence.

There’s also a wonderfully egalitarian feel to Nigella’s pantry as well. Truly high-end and obscure items like that tin of Santo Domingo Sweet-Smoked Pimenton de La Vera are casually sitting alongside something as mundane as PG Tips tea sachets, which in turn sit comfortably behind the tin of imported mustard greens, and alongside the jar of Mott’s. “We are all equal! We are all friends! Never mind the wars that have raged between our nations, never mind the colonial domination of the Mother Country, never mind the infernal sniping and one-upmanship that has long defined Anglo-American relations in spite of a mutual admittance of the need to co-exist. Food is our great equalizer, breaking down walls of misunderstanding and balkanization. These kinds of cheerleading phrases (my own, not Nigella’s) manifest themselves in not only the philosophy of the book, but also in the recipes.

Of course, the book is about good food fast, and so what we are supposed to see in that photo is speed. Many of these items, cocoa powder, mustard, jars of pears in vanilla, olive oil, red currant jam, and so forth, end up in many of Nigella’s recipes, indicating that terrific processed food is indeed the short-cut we need in order to still cook at home but nonetheless do it with record speed. So, to conclude this post, here are some of my favorite dishes from Nigella Express, and I encourage you to check the book out from the library or buy yourself a copy of it so that you, too, can see just where Nigella’s talents reside.

My favorites:

Mustard Pork Chops (which calls for heavenly hard cider, whole-grain mustard and heavy cream)

Turkey Fillets with Anchovy, Gherkin, and Dill (fresh, aromatic, lovely)

Rhubarb and Custard Gelato (an old take on the wonderful rhubarb and custard from nursery days)

Butterscotch Fruit Fondue (what more to say? It will convince children to eat a load of fruit!)

Brandied-Bacony Chicken (a mere three ingredients, and out of this world. I promise!)

Potato and Mushroom Gratin (homey and comforting on a cold winter night).

Go Get ‘em Smoothy (often the way I start my day)