Seated Scribe Louvre, Paris, France

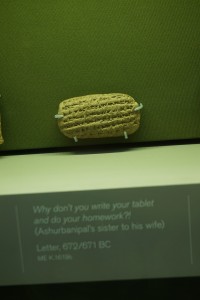

Library of Ashurpanibal British Museum

In preparation for our international study trip to London, Oxford, and Berlin, several trip participants have enrolled in an Independent Study Course, Egypt and the Ancient Near East. Co-taught with Professor Melanie Hull, this 10-week course gives JCCC students a unique opportunity to explore the history, religion, art, culture, politics, language, literature, and the worldview of both Egypt and Mesopotamia concurrently. We are reading primary texts such as Sinuhe and Gilgamesh, digitally exploring museum collections, tracing the developments of the fields of Egyptology and Near Eastern Studies, and examining key objects that we will see on our study trip. For our ancient writing session, we went to scribal school.

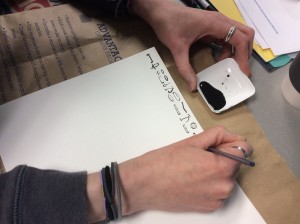

Cuneiform

The purpose of this exercise was to experiment with different writing instruments to see if we could approximate how a scribe in Mesopotamia might have written on clay. For our first experiment, we used air-dry clay. A few things were immediately evident: 1) It takes many years to train as a scribe in a cuneiform language! While we were all successful at making wedge shapes and lines, our marks were neither uniform nor neat. At least clay is a forgiving medium! 2) The shape of stylus matters. We tried a large, square-ended chopstick, a round-ended skewer, and even mechanical pencils. The square-ended chopstick approximated the characteristic wedge shape of cuneiform writing the best.

Museums we will be visiting that hold notable cuneiform collections include the British Museum, the Ashmolean Museum, and the Pergamon Museum.

Cylinder seals

Cylinder seal with the symbols for the moon god Sin, the lightning bolt of Adad, Ishtar’s star, and the seven dots for the Pleiades/Seven Sages.

To make the cylinder seals, we cut a long candle into smaller segments. The students incised their designs with a nail, keeping in mind that the resulting image would appear in raised relief. This gave us all a greater appreciation for the skillful craftsmanship and intricate detail of the ancient cylinder seals.

Museums we will be visiting that hold notable cylinder collections include the Ashmolean Museum and the Pergamon Museum.

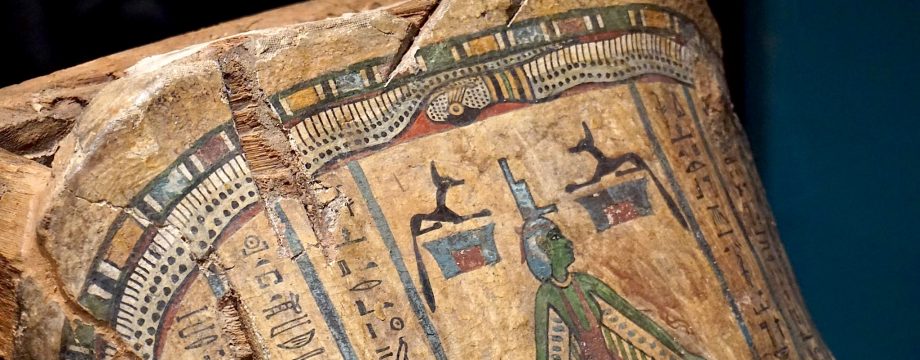

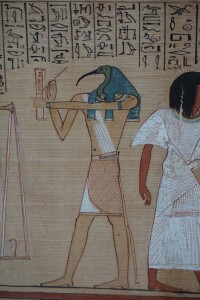

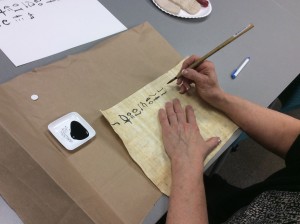

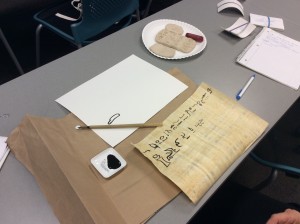

Papyrus

I was extremely fortunate that all of the students had taken my Egyptian Hieroglyphs courses prior to enrolling in the Independent Study. Therefore, we could go beyond the Egyptian “alphabet” or writing our names. Instead, we composed words of gratitude for Djehuty (Thoth), the Egyptian god of writing, knowledge, medicine, and magic (among other things!).

However, what was new to the students was writing in cursive hieroglyphs. When we study hieroglyphs, we are generally reading from a hieroglyphic typeface either in a textbook or in a computer-generated handout. Students complete homework assignments with their own transcription of the hieroglyphic signs. These standard signs were used to carve into stone or another hard material; it was much more common in antiquity for scribes to use one of the cursive scripts such as hieratic when writing with ink on papyrus. For this exercise, we decided to write in cursive hieroglyphs–still very much recognizable as the hieroglyphic signs they derived from. The text we transcribed said “For Djehuty who gave words and script and who gives success to the learned.”

Factors to consider when writing on papyrus is to write on the smooth side (the horizontal lines are more visible), take care with the amount of ink on your brush, the orientation of your hand as the brush connects with the surface of the papyrus, not to hold the brush too tightly, and to work with the motion of the bristles instead of trying to control each stroke. For this exercise we used small detail brushes and Chinese calligraphy brushes. The students did not chew on the ends of a reed pen to make their own brushes!

It was clear by the end of the session that Egyptian and Mesopotamian scribes trained for years to be able to compose an effective text. The rarity of literacy in the ancient world coupled with the artistic and linguistic knowledge that was necessary to perform scribal duties secured the place of the scribe in the higher echelons of society.

I am looking forward to more adventures in experimental philology, and I know the students are as well.