Learning Objectives

By the end of this lesson, you will be able to:

- License a work with a Creative Commons license

Introduction

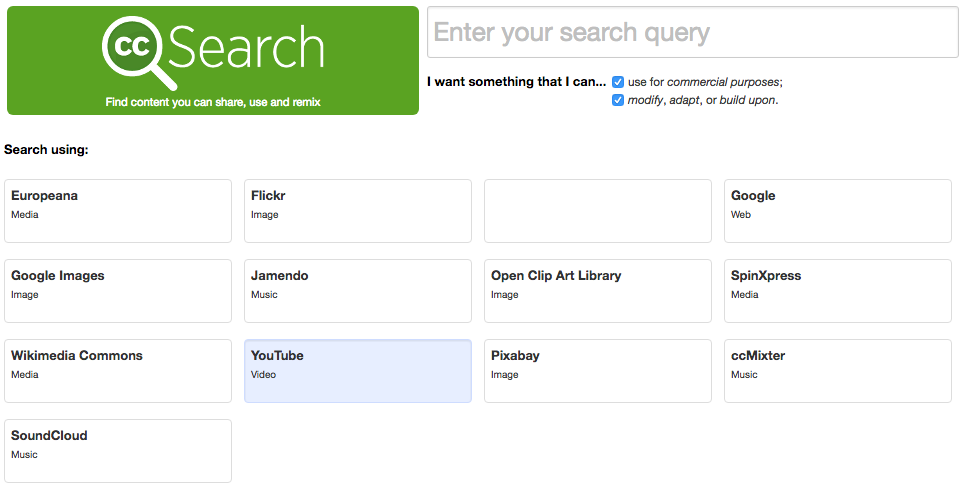

A Creative Commons (CC) license can be placed on a wide range of content, indicating to potential reusers what they are allowed to do with your work. Many content sharing platforms such as YouTube, Vimeo, Flickr, and more have tools for marking content as you upload them. In other cases, you may wish to individually mark content that will be shared in places other than a public platform. This lesson will cover the basics of marking your content with a CC license.

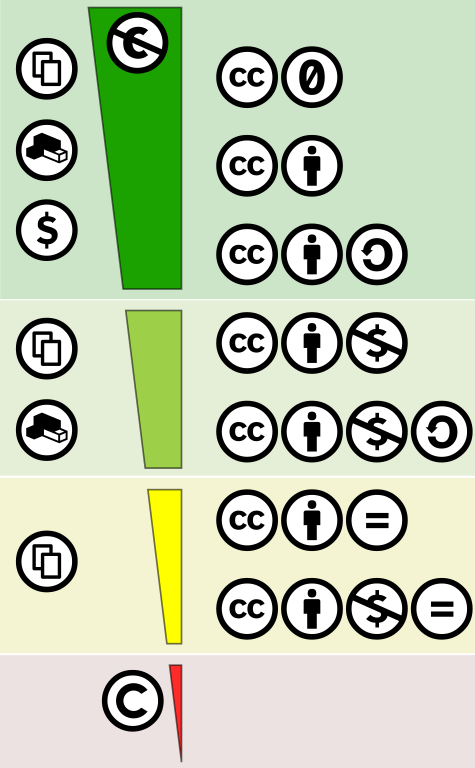

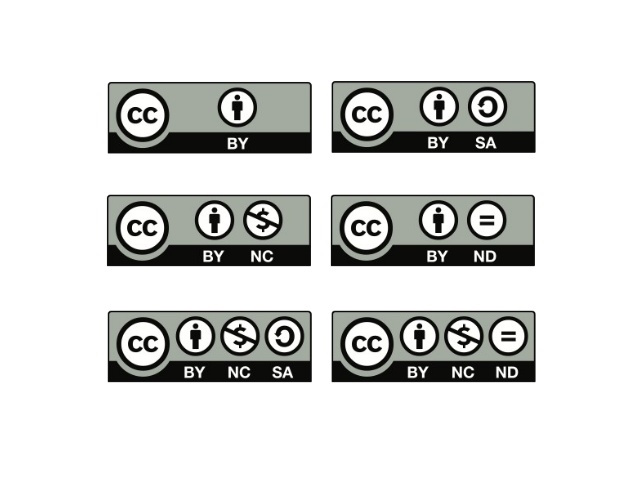

What’s in a license?

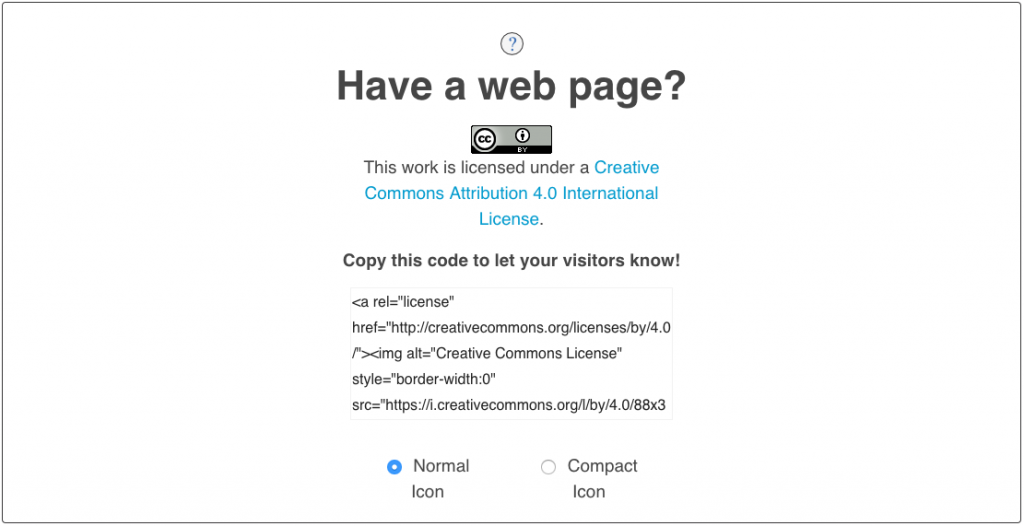

When we “get” a CC license, all we are doing is placing a license icon or statement on our work, and linking back to the legal documents for the license we chose. For example, a CC BY 4.0 license is seen below:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This license was generated by the CC license chooser, and the HTML code from the license chooser was pasted into this webpage. While not a requirement of the license, using the HTML code for the license is the ideal way to mark individual pieces of content with a CC license because it is machine-readable and allows CC-licensed content to be found more easily. As you will see below, using the CC license chooser is not necessary if you provide complete attribution in other forms.

Attribution (TASL)

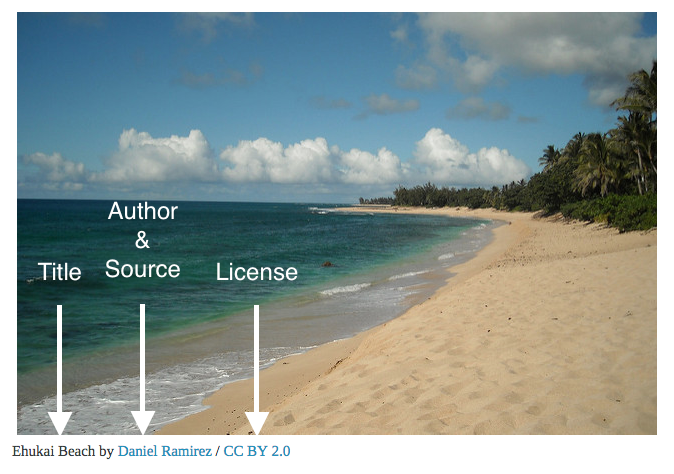

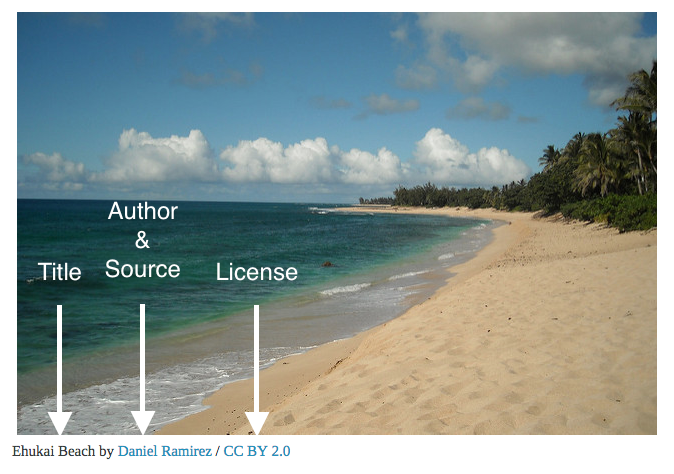

According to CC best practices, proper attribution includes:

- Title

- Author

- Source (link back to creator, if applicable)

- License (name of license and version)

The above is an example of a basic attribution for a single piece of content.

CC License Chooser

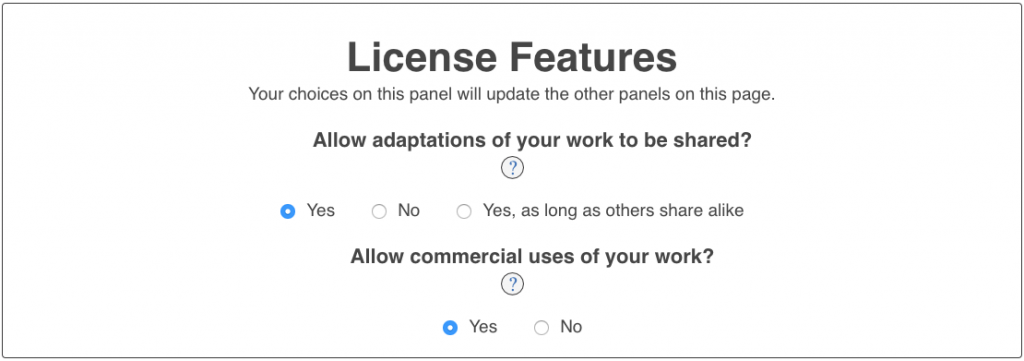

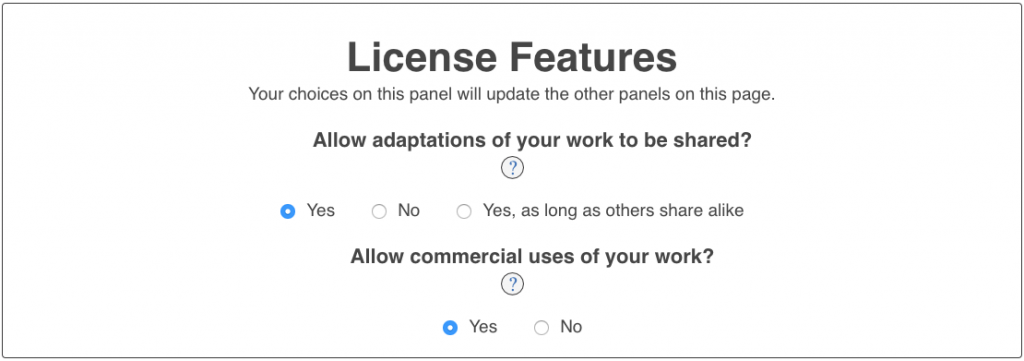

The CC license chooser can make short work of marking your work with a CC license. To begin, go to https://creativecommons.org/choose/.

You will be prompted to select conditions for sharing your work, as mentioned earlier in this chapter.

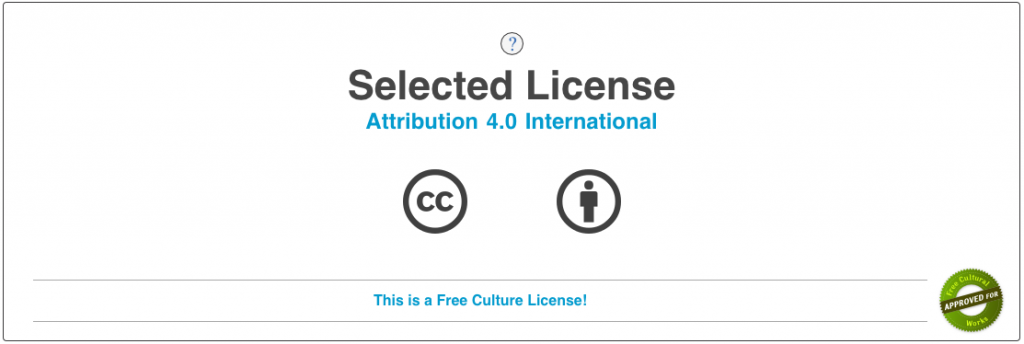

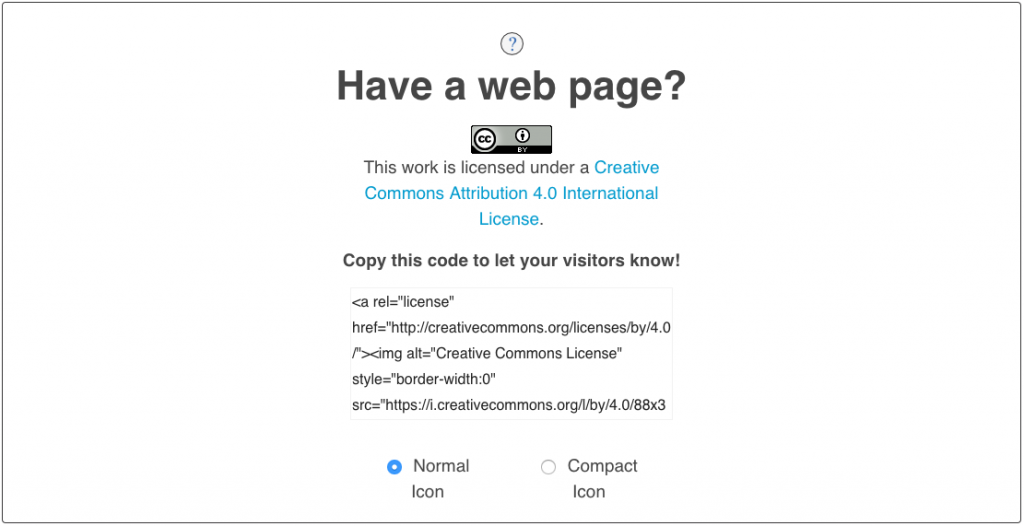

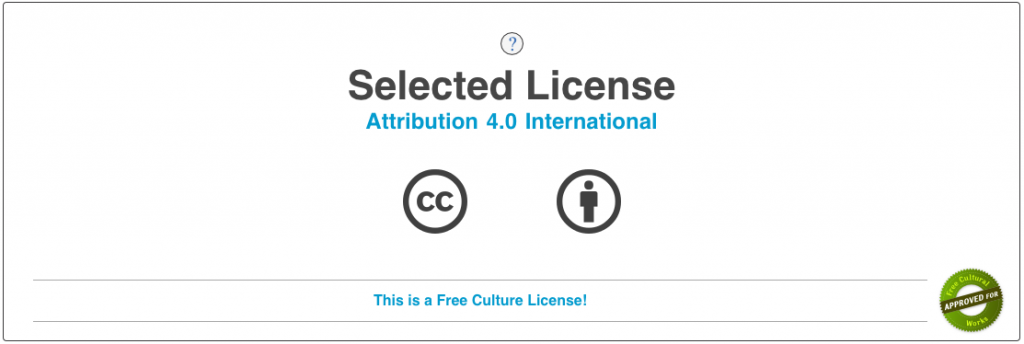

Once you have chosen the conditions you wish to share under, the chooser will show you which license fits your terms:

If this is the license you wish to use, you are almost done. If not, revise the conditions from the earlier step to match the license you wish to share under.

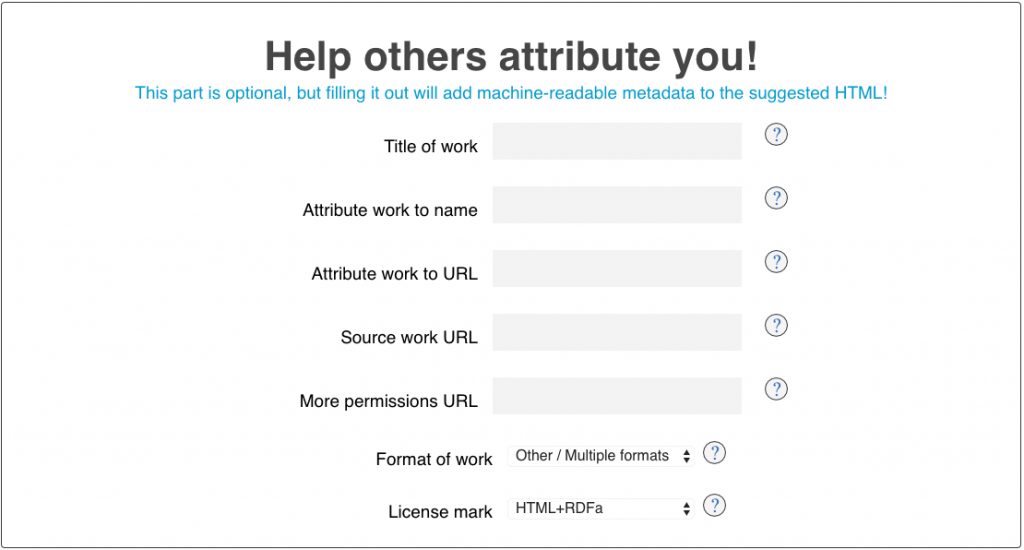

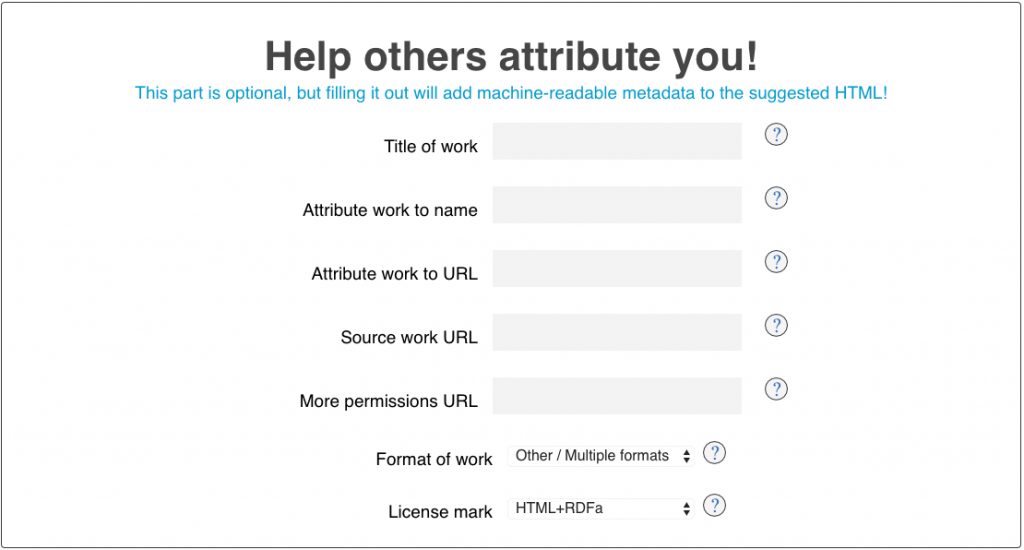

Then, you will have the option of adding descriptive metadata to the license.

Last, you will have the option of having the chooser give you a CC license mark in a format that fits your content well.

At this point, you can copy and paste the license badge and text, or grab the HTML code for use on the Web.

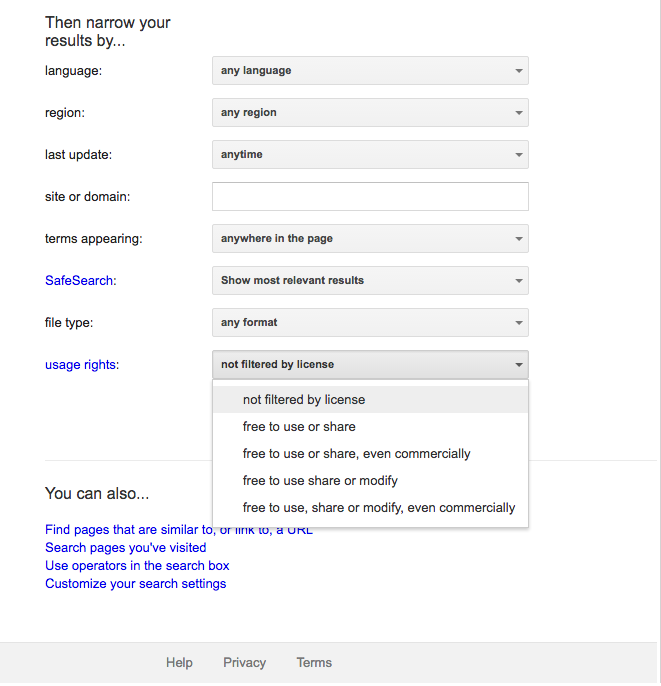

Webpages

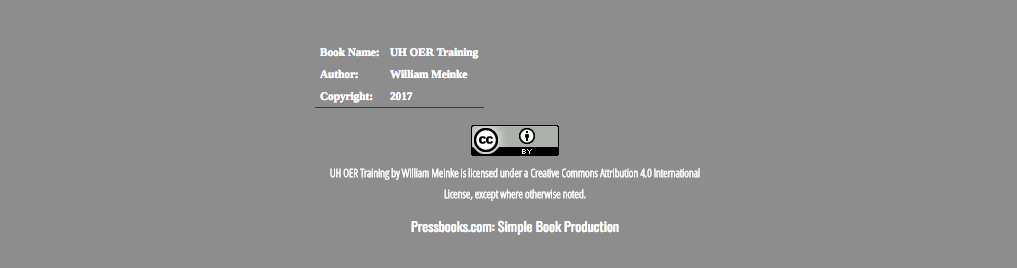

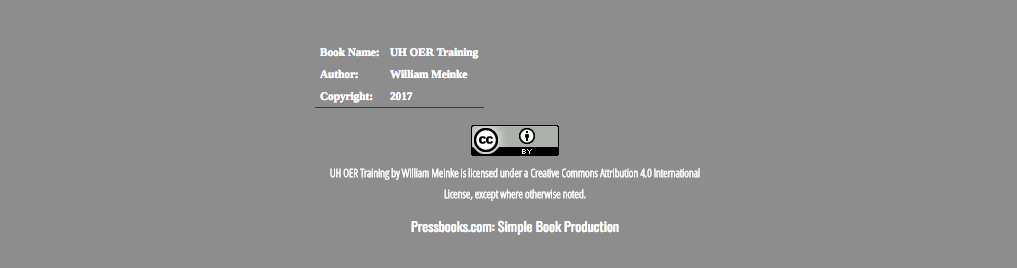

Webpages are often marked with a CC license in the footer or sidebar of the website. The example below is from the Pressbook (website) containing this lesson:

Video

It is simple to use a CC license bumper frame at the beginning or end of a video, or wherever the credits appear. CC license bumpers appear like so:

Offline Materials

Materials intended for print or other non-digital use can be marked with a CC license as well. This is often displayed in the footer of a document, or wherever the copyright statement usually exists. Offline CC license marking does not carry links back to the original work or the license, but it does make it clear how the content is being shared.

Knowledge Check

[h5p id=”7″]