Kate Manne’s Gone Girl has a lot to recommend it. Among its merits is a direct and accessible style and Manne’s original and insightful takes on a number of topics, including some we might have thought were pretty shopworn by now. Manne is also an insightful reader of fiction and a writer who moves between literature, philosophy, and politics with agility. Overall though, the book is an uneven work in my view, and frequently frustrating...Keep reading.

12 Rules for Life: A brief review.

The world probably doesn’t need much more said about Jordan Peterson for a while, but having read his 12 Rules of Life: An Antidote to Chaos from lobster to pen of light I feel a bit entitled. So here’s a brief review.

It is a truly weird book. Enough so that evaluating it is a little hard—it’s not obvious what kind of book it is trying to be, and so it’s hard to find a basis for judgment. It attempts—maybe—to synthesize an astonishing range of material, and kinds of material. Much of what Peterson draws on is interesting and he often explains his sources well. But it is fair to wonder if it’s really possible to reconcile the empirically grounded psychology he appeals to with the rather more, let’s say speculative, depth psychology he is also fond of. Never mind the dragons and chaos and biblical stories and fairy tales. Peterson is awful on feminism but good on embodied cognition. His child rearing advice is sensible and his accounts of his daughter’s struggle with rheumatoid arthritis moving, but one has to wonder how much Heidegger he’s actually read and he understands little of Daoism. On the other hand, his biblical exegesis is suggestive and insightful and his accounts of treating patients in his clinical practice fascinating. And so it goes for 300 or so meandering pages.

In the end it has to be recognized that many readers find something of great personal importance in this book, and it’s worth considering why. In this respect Peterson reminds me of another rigorously trained practitioner of the healing arts who dabbles in a personally charted intersection of science, philosophy, and religion. Substitute Hinduism for Jungian psychoanalysis and subtract the politics and you get…Deepak Chopra.

RIP Ranking Roger

Very sad–but here’s of uplifting ones.

The War Against Parents II

Historically religious liberty has been at the core of liberalism, reflecting its birth amidst protracted religious conflict. This helps explain why concerns about religious upbringings and education dominate recent philosophical discussions about the limits of parental authority. If we assume children’s moral equality, and add to that a desire to treat children in accordance with the same liberal values that we wish to see governing relations between adults, it seems right to suppose children should enjoy the same kinds of religious freedoms. The United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child asserts as much. It seems a short step from here to the conclusion that coercing children’s religious beliefs and practices is as objectionable as coercing the religious beliefs and practices of adults. Keep reading…

The War on Parents

There is no war on parents, though if the work of a growing number of philosophers becomes known to certain kinds of political commentators we may very well begin hearing there is. Careful and creative philosophical work on parenting is increasing, which is wonderful, but it is striking how quickly a range of radical positions is becoming orthodoxy. These include claims such as:

- parents have no moral right to impart their religious beliefs to their children;

- parents should not have a legal right to have their children privately educated;

- parents should not have a legal right to homeschool their children;

- families where two biological parents raise their own children should not be favored over those in which any of a number of different constellations of adults are raising children;

- the moral and perhaps legal standards of minimally decent parenting requires that children not be taught certain things, such as that homosexuality is immoral, or that traditional gender roles are justified by natural differences between men and women.

To be clear, one would be hard pressed to find a philosopher who endorses all these things, but it is easy now to find many thinkers actively arguing any combination of them. Keep Reading…

Against “Indoctrination”

Like a lot of areas of philosophy, philosophy of education is frequently a locus for skirmishes in larger political battles. A common tactic is to accuse one’s political opponents of not really believing in education as shown by their lamentable views on school funding, school choice, sex education, evolution, or whatever. A variant of this tactic is to suggest our sides supports education—that is real, or genuine education—while the others practice indoctrination, is an ugly imposter that resembles education at first glance but which is actually something else entirely. That the word “indoctrination” is mostly doing rhetorical work in these debates is strongly suggested by how readily both sides of political divides use it against their opponents, how similarly they characterize it, and the mutual lack of charity both sides display in trying to make the charge stick.

I think it’s time to retire the word “indoctrination” in serious discussions in philosophy of education. Keep reading…

Chimpanzees and Personhood

There has been a lot of talk of late about whether or not chimpanzees are, or should be counted as, persons. The most immediate occasion concerns a legal maneuver on the part of the Nonhuman Rights Project to get two chimpanzees to be recognized in law as persons. A group of philosophers and others have submitted an amicus brief in support of this motion, and a fortiori in support of the contention that no legally plausible understanding of “personhood” excludes chimpanzees.

I have a lot of sympathy for the practical aims of the HNRP in this case. Given what we know about chimpanzees and the facts of the case at hand it seems likely that the two chimpanzees are being harmed and this should be rectified. However, I find the arguments of the amicus brief unpersuasive and a largely beside the point. Overall they display the penchant of philosophers to confuse the kinds of questions that interest philosophers with questions that are relevant to legal proceedings. I’ll say a few things here about a couple of examples. (Read more)

Podcast on Academic Freedom

Here is an interview I gave with the KNEA on academic freedom.

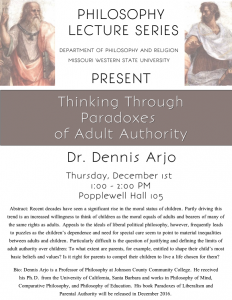

Paradoxes of Liberalism and Parental Authority

My book has been published–that’s a nice thing to be able to say.