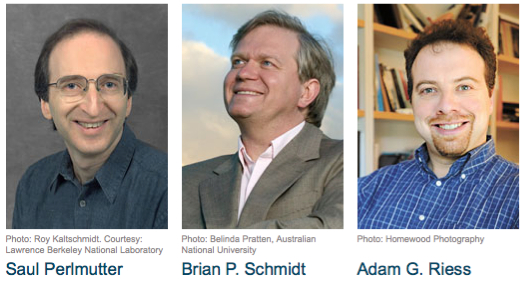

It was announced today that the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics is being awarded to three astronomers for their work on the nature of the expansion of the universe. The following is an excerpt from nobelprize.org.

“The Nobel Prize in Physics 2011 was awarded “for the discovery of the accelerating expansion of the Universe through observations of distant supernovae” with one half to Saul Perlmutter and the other half jointly to Brian P. Schmidt and Adam G. Riess.”

Dr. Patterson and I have been teaching our students about this discovery for years and we have been following the work and results for sometime. It was a stunning and very surprising discovery that countered everything we expected about the expansion of the universe.

They measured distances to galaxies using the measured brightnesses of type 1a supernovae (exploding white dwarfs) and measured the redshift of these galaxies. Using the apparent peak brightnesses of these supernovae, they could calculate the distances to the galaxies where these supernovae occurred. The redshift is used in the Hubble Law to calculate the speed at which galaxies are moving away from us. The finding wasn’t that the expansion of the universe was slowing down in its expansion, as one would expect, but is in fact speeding up!

The cause may be some kind of vacuum energy, often called “dark energy” or “the cosmological constant”. The nature of this energy is a complete mystery and is often referred to as the most important problem in physics and astronomy today.

There is little dispute about the correctness of the measurements. However, the finding all hinges on the idea that all type 1a supernovae explode with identical brightnesses and that nothing like the rotation rate of the white dwarf causes variations in these supernovae.