Visionary: The Work of Michael Brantley

December 13, 2025 through May 3, 2026

Exhibition Catalogue by Harold Smith (PDF)

On the art of Michael Brantley — by guest curator Harold Smith, artist, curator, educator, and writer

“Where there is no vision, there is no hope.” – George Washington Carver

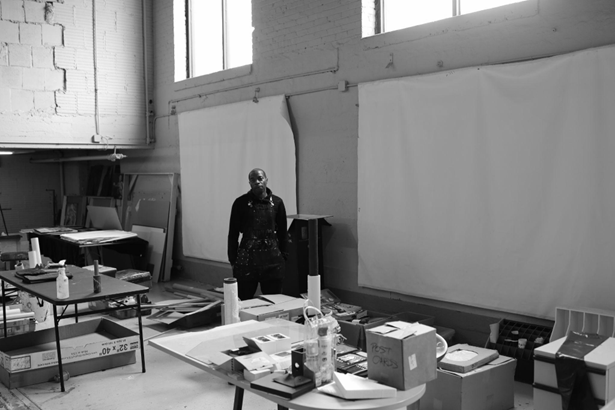

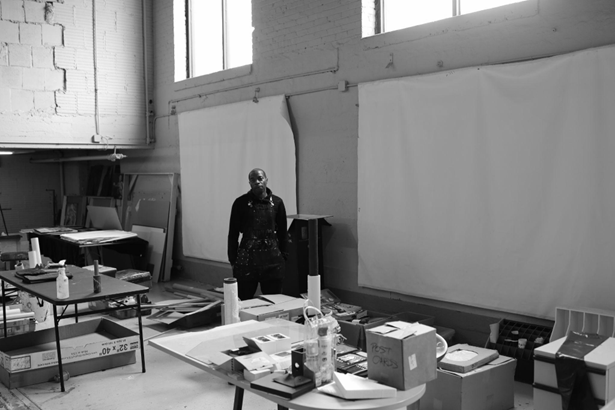

My first visit with Michael A. Brantley was in the cavernous basement of the former Pressman Studios in Kansas City, Kansas. From 1927 to the mid-2000s, this basement housed the printing presses for the once-daily but now online-only Kansas City Kansan newspaper. When the Kansan ceased physical publication, the basement was converted to artist studios. At one point, it housed multiple working artists, each with their own space. Now all the artists were are long gone, except Michael Brantley.

As the space is vast (the Kansan once had a circulation of 34,000), the temptation of many artists would have been to just spread out supplies and projects, since there is so much room to work with and no one else to consider. However, one look, and the intentionality of Brantley, its sole inhabitant, is evident. The entire space is neatly organized, with works in progress strategically placed so that Brantley could focus on each one without visual distraction from the others.

Michael’s office is a compact, somewhat dimly lit yet cozy and inviting space that made me think of the smoky backroom of a speakeasy where the aroma of bourbon is in the air and clouds of cigar smoke hover over clandestine poker games. It was here where Brantley first opened up and peeled back some of the layers of his complex and winding journey to this moment.

We talked for about an hour about his backstory, his education, his influences, and what the work of Michael Brantley is truly about. I left that first meeting with a clear understanding of his work, born of struggle and triumph, synthesizing tradition, realism, and the Black experience.

Brantley’s masterful oil paintings stand as a bridge linking the past and the present, ascending from deep roots in Western art traditionalism and spreading its branches wide to incorporate the lived realities of today’s Black Americans. His duotone photorealistic style synthesizes the intensity of jazz, the struggles and dignity of living while Black, and the complex social dynamics of a community still negotiating what it means to be Black in America. His velvety paintings explode from the collision of classical technique and the contemporary Black experience.

A native of Kansas City who spent time in Detroit, Brantley is best known for his lush renditions of Black jazz musicians. His work has been featured by the NFL, and he has exhibited at the American Jazz Museum, the Nelson-Atkins Museum, The Zhou Brothers Art Center, and now the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art.

Brantley’s career trajectory has been somewhat delayed but not denied by profound personal adversity. In 2015, coming off a breakthrough exhibition at the American Jazz Museum, Brantley was diagnosed with sarcoidosis, a chronic inflammatory disease. Navigating the precarious waters of the Affordable Care Act to secure treatment was a challenge that soon followed. Yet, ten years later, Brantley paints daily with the same dedication and purpose, a testament to his personal courage and creative endurance.

Brantley is a longtime member of the African American Artists Collective in Kansas City, a respected organization empowering Black voices in the Midwest art scene. It was through this membership that Brantley’s work was exhibited at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art as part of the Testimony: African American Artists Collective exhibition in 2021. An artist with deep roots in Kansas City’s Black community, Brantley grounds his artistic practice in his commitment to his community, ethnic heritage, cultural history, and Black artistic tradition.

The African American Artists Collective in 2021, Photo: Jim Barcus, Courtesy of KC Studio Magazine

One of the most impressive aspects of Brantley’s work is that, despite being primarily self-taught, his work reflects a striking adherence to traditional realism. This alone is a testament to the veracity of his artistic practice. A skill set such as Brantley’s is only developed through years of focus, practice, and dedication to perfection. Anatomical precision, exemplary composition, virtuosic use of light, and sophisticated shading speak to an artist who has practiced long and hard at his craft, holding himself to the highest of painterly standards. Brantley’s Caravaggesque ability to utilize light and darkness to dramatize, isolate, and elevate his subjects distinguishes his work from much of today’s contemporary painting while his somewhat understated visual ambiance brings to mind the sense of timelessness observed in the works of Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Goya.

A serious craftsman with unwavering painterly conviction, Brantley wields the tools of tradition with precision and intention for the purpose of elevating Black subjects that were minimized and marginalized within those same traditions. Like Michelangelo using mallets and chisels to liberate forms from marble, Brantley uses the tools of Western art traditionalism to liberate and uplift the Black subject from the social-historical constraints inherent in the canon of Western art.

It is no surprise, therefore, that Brantley cites Henry Ossawa Tanner as an influence. Born free in 1859, the son of a future African Methodist Episcopal Church bishop, Tanner expatriated to France in 1891 and became the first Black American painter to gain international acclaim. Possibly the first known painting by a Black American to realistically depict other Black Americans, Tanner’s Banjo Lesson (1893) utilized realism to present the Black lived experience in a way that challenged the commonly held stereotypes of the time. Brantley, likewise, uses realism to confront and challenge the stereotypes of our time as seen in Figures of Speech (2024).

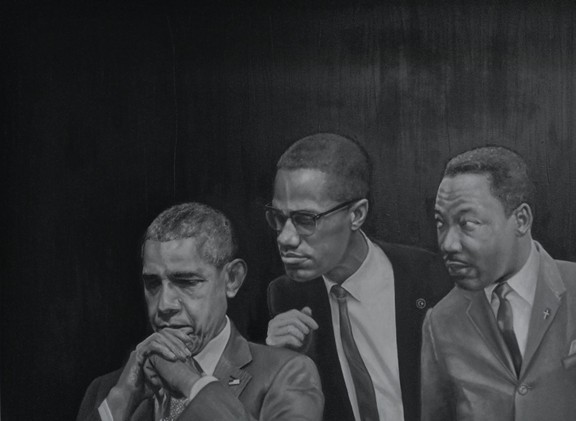

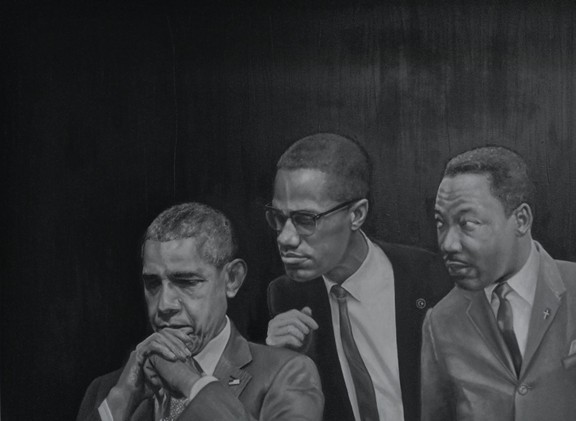

Michael A. Brantley, Figures of Speech, 2024, oil on canvas, Image courtesy the Artist

Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Banjo Lesson, 1893, Hampton University Museum, Gift to museum by Robert C. Ogden

Brantley’s usage of traditional painting techniques to express contemporary Blackness effectively captures the emotionally charged history of Black artistic resistance in a bottle. By using techniques of the Old Masters to immortalize Black musicians and activists, Brantley’s work becomes the physical embodiment of Charles White’s 1940 declaration that “paint is the only weapon I have with which to fight what I resent.”

While Caravaggio used chiaroscuro to dramatize Christian martyrs, Brantley uses it to dramatize the juxtaposition of the Black lived experience against the backdrop of the Black American experience. In that sense, like Caravaggio, Brantley uses realism and tenebrism to transform the martyred, both literally and symbolically, into heroic figures.

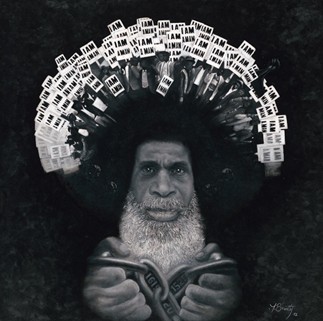

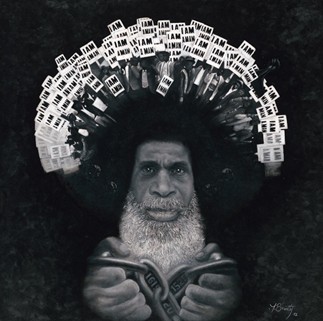

This transformation is evident in I Am A Man (2018), where Brantley uses chiaroscuro to triumphantly crown the subject with the phrase “I Am A Man.” Rooted in the 1968 Memphis sanitation workers strike, this phrase is now synonymous with the demand for civil rights, dignity, and equal treatment. Powerfully simple, it speaks to Black self-affirmation rising like a phoenix from the smoldering ashes of cultural subjugation.

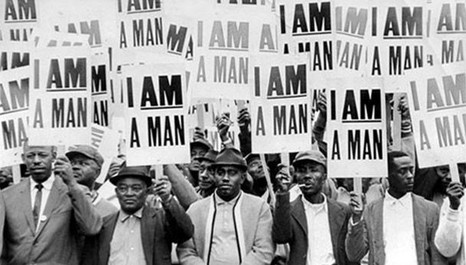

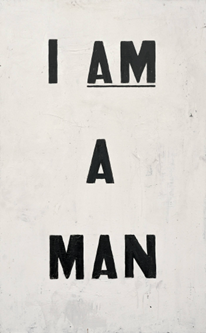

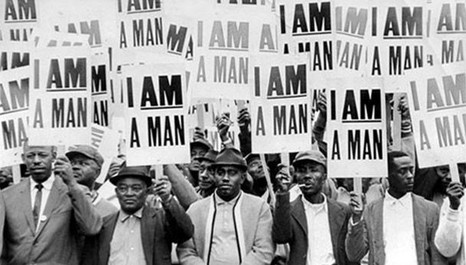

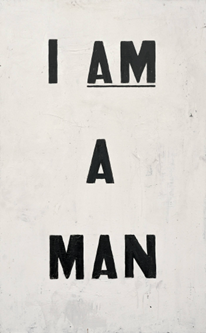

Taken during a Civil Rights protest, Richard L. Copley’s famed 1968 photograph contextualizes “I Am A Man” as an external declaration, publicly asserting one’s inherent human dignity and demand for respect as such. Twenty years later, Glenn Ligon’s 1988 rendition isolates the phrase, allowing the viewer to interpret it based on their own internal experiences.

Thirty years later, Brantley’s presentation of “I Am A Man” as a chorus of affirmative declarations exuding like afro picks from the hair of an aged Black man grasping chains resonates like a choral response to “I am an invisible man,” the opening sentence from Ralph Ellison’s seminal novel Invisible Man. His portrayal of the phrase contextualizes it as an internal declaration, one that exists in and of itself, regardless of public response.

Richard L. Copley, I am a man, 1968, Photographic print

Glenn Ligon, Untitled (I Am a Man), 1988, Oil and enamel on canvas 40 x 25 inches (101.6 x 63.5 cm), National Gallery of Art

Michael A. Brantley, I AM A MAN, 2018, oil on canvas, Image courtesy the Artist

While Brantley wields traditionalism with the exactness of a surgeon’s scalpel, removing the cancers of stereotype and caricature from the canon of Western imagery, his aesthetic ideology stems from the self-determination of Alain Locke and the New Negro philosophy which fueled the Harlem Renaissance. Brantley’s work faithfully picks up the mantle from Locke’s 1925 declaration that, “art must discover and reveal the beauty which prejudice and caricature have overlaid.” In A Seat at the Table and I Am A Man, Brantley utilizes allegory to position Black subjects as heroic figures, analogous to Harlem Renaissance painter Aaron Douglas in The Creation (1927), Judgment Day (1927), and The Negro in an African Setting (1934). When one considers the synthesis of traditionalism and New Negro/Harlem Renaissance aesthetic ideology, it is inevitable that A Seat at the Table and I Am A Man lie firmly within the canon of Black American Social Realism, echoing tenets found in the work of Augusta Savage, Jacob Lawrence, Hale Woodruff, and others.

In A Seat at the Table, Brantley portrays his subjects with natural hairstyles while dressed as domestic servants, visually manifesting Locke’s assertion that art reveals “the beauty which prejudice and caricature have overlaid.” The primary subject’s mouth is taped shut, symbolically silencing his physical voice. Yet, the voice of his humanity is heard through his natural hairstyle. These notions of heroism in the midst of oppression echo those found in the works by Aaron Douglas such as Harriet Tubman (1931).

Michael A. Brantley, A Seat at the Table, 2021, oil on canvas, Collection of John and Sharon Hoffman, Image courtesy the Artist

Aaron Douglas (1899-1979), Harriet Tubman, 1931, oil on canvas, © Heirs of Aaron Douglas / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Brantley’s work is imbued with intricate detail reflective of the photorealism found in the paintings of contemporary Black painters such as Amy Sherald, Kehinde Wiley, and the late Barkley Hendricks. However, Brantley’s emotionally charged references to social injustice differentiates his work from theirs and places it in a category of its own. Hendricks’s North Philly Niggah (William Corbett) (1975) and Brantley’s The First Lady of Song (2012), a rendition of jazz icon Ella Fitzgerald, both utilize a sense of photorealistic detail in portraying their subjects, yet Brantley’s heightened sense of emotion, from the pained facial expression to the singular drop of sweat streaking down the subject’s face, evokes a different, possibly more intimate and visceral response.

Barkley L. Hendricks, North Philly Niggah (William Corbett), 1975, oil and acrylic on canvas, 182.9 x 121.9 cm (detail). Photo © Sotheby’s

Michael A. Brantley, The First Lady of Song, 2012, oil on canvas, Image courtesy the Artist

By painting jazz icons in works such as The First Lady of Song, The Cornet (2025), and Yardbird (2025), Brantley speaks to their centrality, and that of the arts in general, to Black cultural and social identity. By making the humanity of these musicians the focus of the image, Brantley positions the Black jazz musicians as living embodiments of the Black contemporary struggle. He does not emphasize their humanity to the detriment of their artistry but rather affirms that Black artistry and Black humanity are inseparable. In Brantley’s work, Black humanity and Black artistry are analogous to light and heat; they may be separate qualities, but you cannot have one without the other.

Michael A. Brantley, Yardbird, 2025, oil on canvas, Image courtesy the Artist

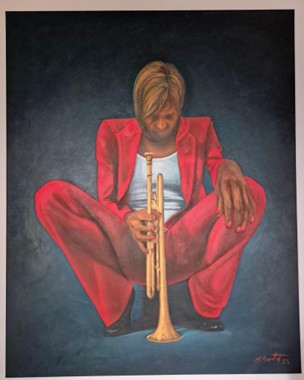

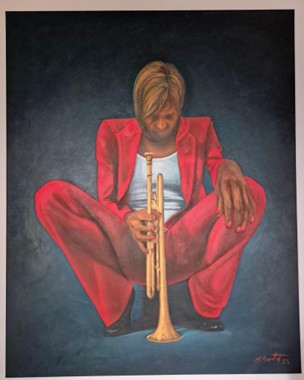

In The Soloist (Trumpette) (2024), a painting of a seemingly exhausted or reflective woman trumpet player, Brantley departs from his normal duotone palette, utilizing soft crimsons and browns. This grounded position of the subject speaks to the connection between vulnerability and the power of the vulnerable, an uneasy relationship shared by the dispossessed. An emotional weightiness exudes from the image, as in most of Brantley’s work. The departure from a duotone palette shifts the emotional weight from the subject to the entire image itself.

Michael A. Brantley, The Soloist (Trumpette), 2024, oil on canvas, Image courtesy the Artist

Michael A. Brantley’s work synthesizes Western painting traditionalism and the contemporary Black experience. Ideologically speaking, he is firmly planted in the ideas guiding the Harlem Renaissance, Social Realism, and the Black Arts Movement. By portraying both the famous and the unknown, the easily recognizable and the nameless, Brantley affirms the shared experience of Black Americans.

Brantley’s paintings remind us that artistic tradition is not written in stone. It is changeable and continually evolving. In his work, prior traditions become tools for creating new expressions that not only articulate the Black experience but speak to the shared human experience itself.

The work of Michael A. Brantley is both for this time and also timeless. His work honors the past, paying homage to both cultural and artistic traditions, while speaking to power in the present.

References

Locke, Alain. The New Negro. New York: Albert and Charles Boni, 1925.

White, Charles. Interview in Art Digest, 1940 in The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.3, no.4, December 2009, https://www.jpanafrican.org/docs/vol3no4/3.4CharlesWhitebyPaul.pdf

Ellison, Ralph. Invisible Man. London: Penguin Books, 2014.

Michael A. Brantley, Love Still Remains, Oil on canvas with acrylic flakes mounted on wood, 2025

Michael A. Brantley, Say Whaat? (The Tea), 2025, acrylic and oil on canvas, Image courtesy the Artist

Michael Brantley in his studio