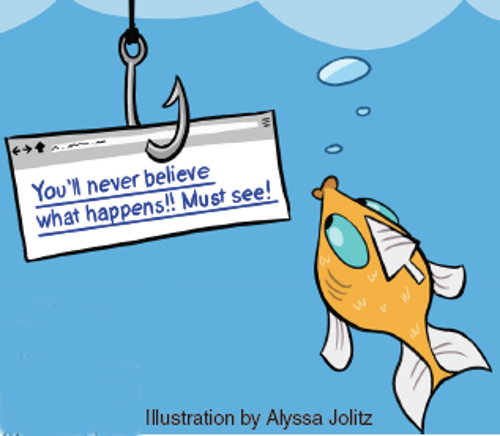

Or, probably not. The point is, click-baiting works.

By Christina Lieffring

The hype and hyperbole of click-baiting was once relegated to spam, tabloids and dubious advertisements. Then entertainment websites such as Upworthy and Buzzfeed discovered that promising to “blow your mind,” “make your jaw drop” and generally stupefy generated clicks that turned into shares on social media turned into revenue. Now sensationalist headlines are creeping onto the websites of legitimate news sources. Or so the story goes.

Maureen Fitzpatrick, who teaches Writing for Interactive Media, said when she first saw these articles in her Facebook feed, “I never clicked on it because I assumed it was the kind of junk you get on the right-hand column […] But then they were populating more people’s [newsfeeds] and none of them were screaming about getting viruses.”

She grew to trust and click on these links because her friends kept posting them.

But, Fitzpatrick explains, the relationship between social media and click-baiting goes deeper when you take into account Search Engine Optimization (SEO), the tactics websites use to gain a higher ranking on Google, Bing and other search engines. According to Fitzpatrick, your website’s rank in a search engine is partly calculated by how many people click on and share your link. Thanks to social media, this information is easily monitored, giving companies a concrete method for tracking what works. They aren’t formulaic by accident or due to laziness; it’s because they created and use a formula to game the system.

Twitter feeds, Facebook pages and Tumblr blogs are all devoted to mocking click-baiting. HuffPo Spoilers pokes fun at baiting Huffington Post headlines by revealing the surprise. Downworthy is an app made for Chrome that mocks Upworthy’s formula by changing phrases such as “blow your mind” into “might perhaps mildly entertain you for a moment.” And when CNN tweeted, “14-year-old girl stabbed her sister 40 times, police say. The reason why will shock you,” they came under fire from several other news outlets.

Patrick Lafferty, an interactive media professor, admits the links are “annoying” but doesn’t see anything wrong with news outlets adopting these methods, nor does he see it as anything new.

“When you had the paper boy standing on the street corner in major metropolitan areas saying ‘Extra! Extra! Read all about it!’ What is read all about it?” he said.

Emily Alley of the Journalism department agreed.

“You go back to 1900s ‘yellow journalism,’ I feel like it speaks more to human nature than the advertising industry. People want to be entertained. They don’t want to have to look for the story, they want to be slapped with the story.”

Lafferty said the strong reaction from journalists toward news sources using link-bait is due to their “romantic” ideals about their profession.

“They are thinking, ‘We should be writing our stories for the greater good.’ And when you say, ‘I’m writing this in such a way so that people will click on a link so we can get an extra two cents in revenue from the ads side when we get that much more traffic,’ [they are thinking] ‘Hey, we’re supposed to be above the fray.’”

Journalists may also be upset because these headlines seemingly blur the lines between entertainment and hard news according to Alley. While Upworthy is informative, their audience visits the site mainly for entertainment.

“[When readers see Upworthy headlines at a legitimate news website], people might be upset because they might see that as a violation of their audience,” Alley said. “If people want to see the news, they don’t want to see a distraction that’s just for entertainment value.”

Fitzpatrick, Lafferty and Alley agreed that the value of the content is one reason they don’t take issue with the tactic. If you’re baiting audiences into consuming valuable information for the greater good, the methods are forgivable, and according to Fitzpatrick, the methods will change when SEO changes. Future headlines may not use the same tactics, but they will have the same goal.

“Human beings are incredibly creative when they are highly motivated,” Fitzpatrick said.

Consumers strongly react to Upworthy-esque headlines because they can tell they are being marketed to, Fitzpatrick, Lafferty and Alley said. It’s a strange conundrum: click-baiting is formulaic, obvious marketing in a marketing-saturated society with savvy consumers who are aware when they are being marketed to. But we still click it.

Lafferty explained how you catch a raccoon.

“You drill a hole in a log, you put a piece of shiny metal down at the bottom and you nail a nail in at an angle so that just enough of the tip sticks into the hole. The raccoon, being the inquisitive creature that it is, will come along, see the shiny metal, stick its hand in the hole to get the metal and it can’t pull it’s hand out because it gets jabbed by the nail. But no matter what that raccoon will not let go of that shiny piece of metal. Because it loves the shiny.”

So do we.

Contact Christina Lieffring, staff reporter, at clieffri@jccc.edu.