Connor Heaton

Staff reporter

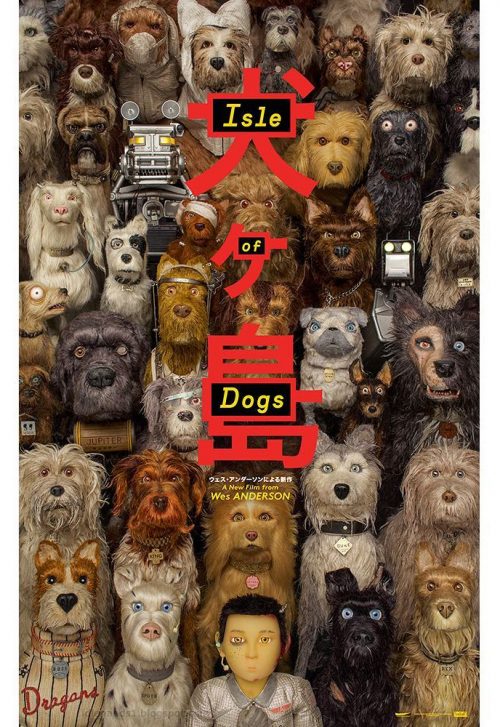

Brilliantly animated, expertly directed and astonishingly intricate, director Wes Anderson’s “Isle of Dogs” is a bold, quirky, sometimes underutilized, but always exciting ode to canines and their deeply human connection to us — through thick and thin.

“Isle of Dogs” takes place in the fictional Japanese archipelago and the towering metropolis of Megasaki. After an outbreak of a dastardly disease known as snout fever rips through the dog population, owners and city officials alike deport all dogs to a desolate wasteland of garbage — fittingly named “trash island.” Dogs here are left to fend for themselves in this harsh world, fighting for every single scrap of trash they can sink their teeth into.

The film centers around a pack of these ravenous alpha dogs, led by their leader, a stray named Chief (Bryan Cranston). The dogs stumble upon Atari, a junior pilot who crash lands on the island in search of his lost dog “Spots.” From there spawns a tale of friendship and loyalty that spans across the island and beyond.

This is very much a story about the bond that grows between Atari and Chief, who after being a stray all his life, is not entirely welcoming of a human master. “I bite,” he growls when Atari reaches to pet him.

The story takes interesting turns and has something to say about companionship and undying loyalty. There is a surprising amount of raw emotion depicted in the film, and it’s astounding given the fact that most of the writing is delivered through Wes Anderson’s signature stilted dialogue.

Much like Quentin Tarantino, Stanley Kubrick or Christopher Nolan, Wes Anderson is one of those filmmakers whose style can be spotted from a single frame. His shots contain symmetrical composition, bright colors, and a preciseness to every movement that feels almost mechanical. Anderson has a style and has kept this little bag of tricks throughout his entire filmography.

Some of his movies rely on it as a crutch, sometimes feeling more style over substance, but here, it lends wonderfully to this world and medium of stop motion. In regards to the world, an interesting decision was made to make all Japanese voices without subtitles, adding to the language barrier between dogs and people.

However, because of this, its signature stilted writing doesn’t always match up with the zany events depicted and almost feels subdued and the tone does not always properly reflect more intense moments. Furthermore, the film isn’t particularly gut-bustingly funny — at least in the vocal department. It feels as though the voice work by acting legends like Bill Murray, Jeff Goldblum and Edward Norton aren’t properly utilized, probably because their characters don’t have much to do.

One possible explanation for this exists within the lore of the world, in which most dogs sent to trash island were once bound by a master and are eager to receive direction and become obedient. Perhaps because of this, when the boy enters the story, all other dogs, aside from Chief, sink into the background and are content with being led.

The traditional Japanese inspirations echo across the entire production, from the setting to the music, which favors low, pounding drums over bombastic Western orchestras. Watching it feels less like watching an animated children’s flick and more like watching a play, with all such detail and nuance.

It’s impossible to describe how immaculate and gorgeously detailed this film is, even more so considering it’s animated entirely in stop-motion. Though cobbled together with clay, everything feels alive and like it belongs in this self-contained world.

The amount of detail infused into every character is astounding. For example, during close ups of the dogs’ faces, fleas worm their way in and around the fur, painstakingly fixed into place strand by strand. One can see every fiber of matted hair, each scar, bruise and torn ear.

These are not puppets, these are living, breathing creatures with stories to tell.

Each set piece, hand painted, each figure, moved slightly one frame at time, each second of footage containing over a days’ worth of work by a team of hundreds if not thousands of artistic experts.

Because of all this, in a way, “Isle of Dogs” is one of those rare films whose artistic merits almost overshadow the qualities that make it an objectively amazing movie. It stands on its own and is a production, story and experience I won’t soon forget.