Visiting artist inspires fine art students and faculty to make their mark on the world.

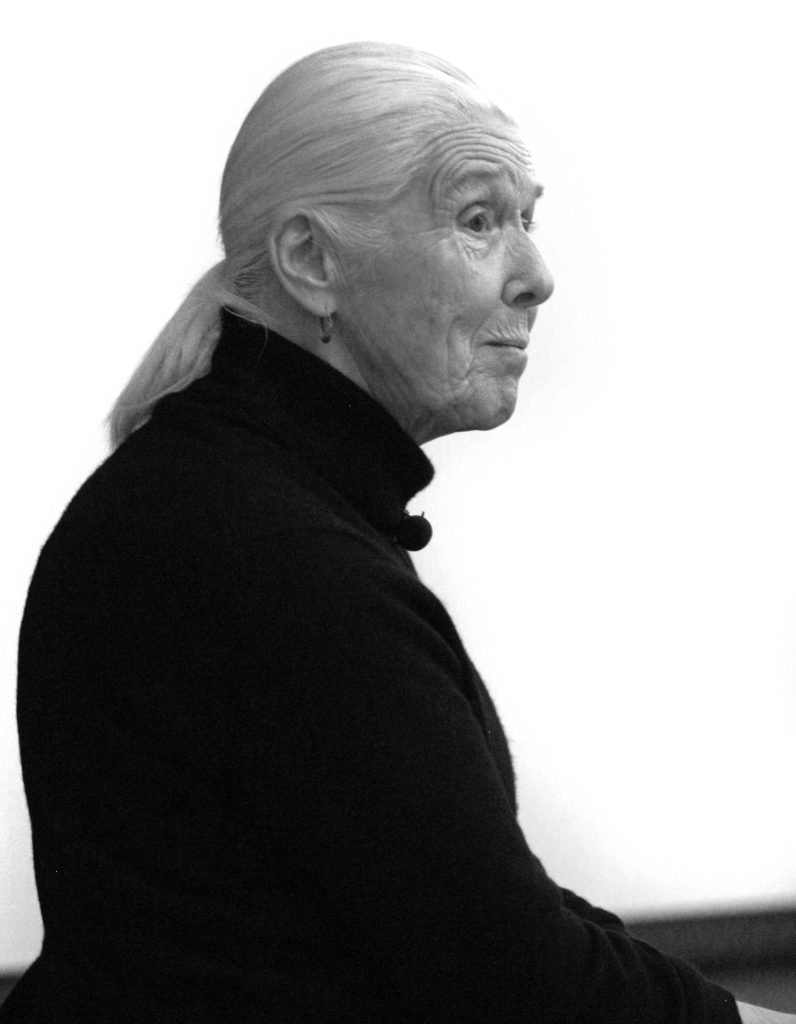

On Thursday, Feb. 6, the Jerome Nerman Lecture Series presented Harmony Hammond in the Hudson Auditorium. Hammond lectured about her artistic process and six decades of activism.

The series gives the community, faculty and students direct access to nationally and internationally renowned artists like Hammond.

Hammond is one of the most historically significant artists, activists and educators in the feminist art movement in the United States and a prominent contemporary artist. Her work is currently on display in the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art’s “queer abstraction” group exhibition.

Things came full circle when fine art department chair Mark Cowardin, a former student of Hammond’s at the University of Arizona, Tuscon facilitated her visit to the college. Cowardin was hired to teach sculpture by professor of art and acting fine arts chair Zigmunds Priede (retired). Hammond was a student of Priede’s in the 1960s at the University of Minnesota.

During her visit, Hammond engaged museum guests at a pre-lecture reception in the museum’s atrium, was the guest of honor at a private dinner in Café Tempo and met with a select group of students and faculty to discuss their work.

Fine art professor Misha Kligman became familiar with Hammond’s work when he learned she was coming to the college. He was excited that he and his students would have the opportunity to meet her. The fine art faculty was tasked with selecting students to discuss their work with her.

“Time was limited, so not everyone was able to critique with her. We had to be selective. I tried to pick work that was advanced enough and artists [who are] at a certain level that could hold a conversation with her. All the fine art disciplines in the department were represented in the selection who were recommended by the faculty.” Kligman said.

Being a professor herself Hammond was generous in sharing her experience and expertise.

“Harmony was excited to talk to people. [She] gave the students feedback which they took in,” Kligman said. “Whenever we have visiting artists coming through, we have them meet with the students. It’s a graduate school or art school experience. We’re pretty lucky to have this going on.”

The level of Fine Arts education students receive at the college is unique.

“This is not a typical experience for a two year [college]. Even a four-year school is not always providing students with these opportunities,” Kligman said. “A variety of perspectives that you get on your work is important. You get to hear outside voices reflecting… people who are making work that is not like yours, people who are not like you. People whose work is in major museums, who have careers talking to you about your work, I think is awesome. That is how one sort of begins a career themselves.”

Tonia Hughes, associate professor of film-making and photography, said the critiques were done privately between Hammond and the students. She explained,

“Critiques can get incredibly personal and you always feel a certain amount of vulnerability. I wanted to make sure they had total privacy. They were one-on-one… . They are very much a private thing. I felt very comfortable and confident with the fact that Harmony Hammond is also a professor… . I knew she would do well with students that she would be honest and up front with students, and at the same time be kind.”

Hughes said her student seemed somewhat starstruck by the experience.

“She was incredibly generous with her time both with students and with us. I had the opportunity of meeting with her about my work too.” said Hughes.

“I am currently doing some work with my mother about the connection and lineage between women. The passing of love and of information and of encouragement and all those things. [I am] thinking about the Greek mythology of the mother, maiden and crone.”

Hughes recently began exploring female lineage as a theme in film making. She shared raw, uncut footage right out of the camera. Hammond was encouraging about the new work and impressed with a photography series Hughes had not worked on for several years.

Hughes’ beloved brother James Earl Miles, nicknamed Bud, died six years ago. He had Down Syndrome and was the heart of her work for many years. She described him as her muse, her light and her joy. After his death, she tried photographing other people with Down Syndrome, but it was a painful reminder of her loss.

“She seemed very interested in the work I am doing with people with Downs. It’s been a while since I’ve done that.” Said Hughes.

Hughes has felt called to continue that work. Her critique with Hammond has her thinking it may be time.

Adjunct professor of fine art Bridget Stewart attended the reception and lecture. During the 2019 fall semester, she lost her mother Mary Frances Stewart. Like Hughes, Stewart found Hammond’s visit inspiring.

“I have not done any artwork since May because of the diagnosis and death of my mother from lung cancer. I just haven’t been able to bring myself to start up again. However, seeing Harmony Hammond’s work started a spark in me that has led me closer to start working again.” Stewart said. “As a printmaker, I of course love process. So, when she was getting into her process and how and why she manipulated the materials, I really felt the urge to create for the first time since May. And, it reinforced my desire to have my next series of prints that I have in mind be large and deal with a tactile surface.”

The deeper impact of Hammond on Hughes and Stewart is certain to come through in their work and the way they show up in the world.

“She is an incredible artist…hearing her talk about her work was phenomenal. I enjoyed getting to know her and hearing her stories.” Hughes said. “I identify as part of the queer community. She is of the generation that forged acceptance of my world both as an artist and just as an activist in the community. It was incredible sitting and just hearing those activist stories. That was wonderful in addition to always, always, always loving her work.”

“I got to talk to her for a bit at the reception before her talk and I found her to be lively, genuine and funny,” Stewart said. “We talked about printmaking. And I will say that in the past I have met artists whose work I admired only to realize they were kind of jerks. That is always a disappointment. Harmony Hammond was a delight.”

When Stewart was in graduate school there were only two women on the faculty and art history textbooks were nearly void of women artists. That is slowly but surely changing because of feminist artists like Hammond who paved the way. Stewart shared what she learned from Hammond.

“[There is an] undeniable power of

women’s art in spite of our exclusion in galleries, museums and literature for the better part of the 20th century. That age does not dull curiosity, that working large, abstractly and with big, heavy, materials is not strictly the domain of male artists although often it is categorized as such, that social commentary through art does not always have to use a narrative visual language, that undeniable ‘presence’ can push a social commentary forward,” said Stewart.