On Thursday, October 3, studio artist and arts educator David Platter, lectured in the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art’s Hudson Auditorium, visited the new FADS building and engaged in meaningful discourse with Mark Cowardin’s sculpture class. The Jedel Family Foundation Visiting Artist Program made the current exhibition in FADS possible and gives students the opportunity to learn from contemporary, working artists like Platter.

Platter is a sculptor and educator, most known for challenging social norms and fostering cultural diversity and meaningful discourse through art. He has collaborated with civic and religious leaders in the United States, France, Egypt, Israel/Palestine and Switzerland. His work is featured in 40 private and public collections across the world.

Platter said, “Art has been a fantastic diffuser that enables what some consider polemic belief systems to be discussed and even united under common values.” Platter is interested in socially engaging projects that open conversations, explore diversity and promote cultural inclusion.

In 2007, Platter took a sculpture class for fun and it changed the course of his life. “I had finished my undergraduate [degree] the year before and was really interested in exploring other mediums and processes. I happened to stumble upon a sculpture course [at the college] … Mark showed us this technique where you could vaporize foam with just the heat of the metal and the metal would replace the void so you ended up with a metal casting of what you’d created with the foam … [he] fostered that pursuit of transformation and transference and once it became clear we could do that with sculpture, I was pretty much hooked.”

Platter went to graduate school at the University of Kansas (KU) as planned. After a year of studying scenography, he enrolled in a graduate level sculpture class at KU. He continued his studies while simultaneously taking graduate level sculpture classes until one of his mentors raised questions that ultimately led to the realization he was at a major crossroads and there was no turning back.

“It took me a year after that to dive in full time to sculpture but it began in 2007, in Mark Cowardin’s sculpture course.” Platter’s life before art was quite different. He said, “I had a more analytical and compartmental way of describing and evaluating life and purpose. It was more mechanized-like, first you do this, then you do that, and it somehow leads to a happy life. Maybe that works for some people, I don’t know how many people it actually works for, but it wasn’t working for me. I didn’t realize it wasn’t working for me until I saw another option. The more intuitive and expressive way of thinking was yielding a learning I wasn’t getting the other way on the trajectory I’d been on.”

“It was more analytical and fixed, like I was moving through a program rather than through an intuitive journey through life…My world started to shift in a way I had not given consideration before. I think art as an expressive tool helped me better process the world around me and myself.”

Platter earned a Master of Fine Arts (MFA) degree from KU with distinction as an Outstanding Achievement award recipient from the International Sculpture Center.

Platter studied Cultural Anthropology and Sociology as part of his undergraduate work and visited Egypt in 2005. He had a visceral response to one of the King Tut artifacts and the monumental, mythical and ethereal depictions of ancient rulers and the exquisite sophistication and craftsmanship of the 4000- year old sculpture he couldn’t quite articulate for many years.

“With most of the Egyptian portraiture, which no one would have referred to as portraiture at the time, they are designed to be ethereal. They are somewhat not real and real at the same time. They are sensitive to the way flesh works but they aren’t too fleshy [as if to say] we don’t want to be too fleshy because we are talking about immortality. We want these images to be immortal.”

Platter didn’t understand it at the time, but once he learned what was possible in sculpture, he realized he could draw from his experiences in Egypt to explore his ideas about connection and equity.

“We have these social hierarchies that exist. And they’ve existed I imagine since humanity. So, I see those social hierarchies in ancient work, I see it in modern work and I just wonder, does that create an avenue for connection or does it inhibit genuine connection? Or keep us separate? I think they are designed to keep us separate. I am really interested in what that is doing to us.”

These are the kinds of questions Platter raises in his work. Admittedly he has more questions than answers, but his process is on-going and viewer reciprocity and engagement are part of it. He creates a safe space for civil discourse and invites us to consider the true value of art as he did when he visited Egypt.

“My appreciation and admiration for the process somehow made it feel close to me, whereas the material like gold, has nothing to do with what it took to make it. I love thinking about the material side of it but not the value of the gold. Platter said, as soon as it becomes monetary it creates distance and no longer holds the same meaning for him. “That creates that hierarchy, that distance for me that I saw in 2005, before I ever made a sculpture. I didn’t have any way to articulate it.”

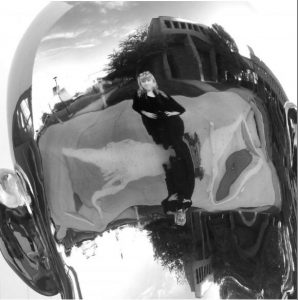

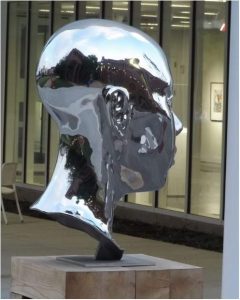

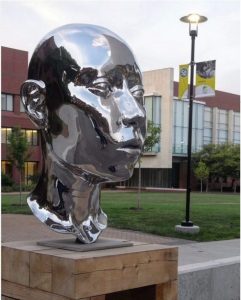

Years later, he was able to express it through sculpture. Myself and Other, the stainless steel sculpture in front of the FADS building was Platter’s direct response to his experience in Egypt. “The formal elements of it was my version, if I were going to do this thing now, this is how I’m going to do it; the sculpture and the relational quality between myself and other, when we look at it, we can’t help but see ourselves, others and the world around us.”

According to Platter, the piece speaks directly about the impact and influence others have on our interpretation of reality, how we view ourselves and how we associate and identify with another person or another space. He was inspired by Anish Kapoor’s Cloud Gate in Chicago and the formal elements of ancient Egyptian sculpture. Platter wanted it to be larger than life but in a way that explored connection and inclusion. It is impossible for one to view the sculpture without becoming part of it.

The placement of Myself and Other allows viewers passing by to first see their own reflection in the back of the head, then seeing themselves in the “other” when they are confronted with the frontal view of the face. This was the first time the artist has been able to explore this presentation of the work.

Sculpture student Gaylin Nicholson, saw himself reflected in the artist’s story and said to Platter, “It is inspiring to hear you say that because it relates and sounds so similar, to what I’ve been, experiencing and I felt so really isolated in this. At the beginning of the semester, [Mark told me] ‘you see that head out there? The guy who made it has a similar story.’”

“Mark grabbed a hold of me the same way last semester. Scenography was my whole approach and I was ready to go to North Carolina the next semester. I took a watercolor class and drawing class for fun and when Misha saw how I was seeing space, suggested I take a sculpture class with Mark. I did, and I was done with scenography,” Nicholson said.

For Platter, it isn’t the monetary value of art as an object but rather the human connection, the alchemy and the transformative power of art that is more precious than gold.

The Jedel Family Foundation Visiting Artists Exhibition will be in FADS through October 25th.

Story by Penny Thieme