Pete Loganbill

Features editor

A seventh grader walks into the school lunchroom. He’s the new guy, his family just moved into town. Scanning the room for a place to sit, he spots another guy with a Dungeons and Dragons monster manual, something he is quite familiar with. The student walks over and says, “Can I sit with you? I play D & D.”

“This Saturday, I’m going to his 50th birthday party that his wife is throwing,” Philosophy Professor Omar Conrad said. “He’s my oldest friend.”

Conrad has been intrigued by Dungeons and Dragons and other board games for nearly 40 years. He and his friend from middle school started a weekly game group that meets to this day. While Conrad now uses similar ideas to teach his classes that he does while playing a game, his parents were worried when he first started.

“At the time, I think it was Geraldo Rivera [who] had a special called ‘Games That [Can] Kill,’ and it was very critical of games like Dungeons and Dragons,” Conrad said. “There were tracts on the evils of Dungeons and Dragons. My parents were pretty concerned. My dad and I had a conversation about it, and I explained to my father, ‘Dad, I get straight A’s, I don’t do drugs. If either of those things change, then you can criticize me for playing this game.’ He conceded the point and allowed me to play the game. [It was] very mature on his part.”

Today, the weekly Dungeons and Dragons group is comprised of six men around age 50, each with a different worldview. There’s a Catholic, a Protestant, an atheist, an agnostic, one who is influenced by Christianity and Unitarianism, and one who at least used to be Protestant. This makes for interesting discussions when a few of the members meet for dinner before they play.

“There’s different dynamics in the group,” Conrad said. “It can vary quite a bit. A few weeks ago, we had a very heavy conversation about … suffering and the existence of God, and the possible purposes of suffering. Whether we can believe in a good or just God, given that there’s suffering. On that evening, everyone at the table was someone who believed in God, so it made a pretty interesting conversation among the three of us for that reason.”

When Conrad plays a game, he likes to play the game the way the maker intended. He practices a similar idea of understanding when he teaches the work of a philosopher, which he finds difficult to do when he believes the writer is mistaken.

“A lot of times when we play games, we play games where the rules could be changed,” Conrad said. “I’m OK with changing the rules of a game, but I do think that you need to play the game according to the rules long enough that you start to get insight into why the rules are as they are before you start modifying them. I try to be as sympathetic as I can to whoever I’m teaching. Interpret them in the best possible light, use examples that make their conclusions, and the way they make their conclusions, seem reasonable. Try to build analogies to everyday things that might make this reasonable.”

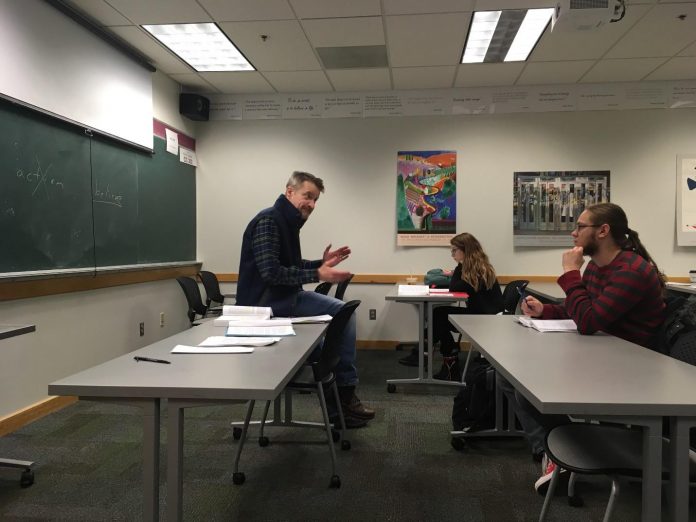

Student Hannah Uebelein said this style of teaching peaks her interest in subjects that do not otherwise intrigue her.

“I would describe Omar’s teaching style as very open,” Uebelein said. “His main focus would be to have the student see from the eyes of the philosopher. I love that he’s not biased, he never gives his personal opinion, but he’s very personal with his examples, and he uses that to help the students learn. I didn’t think I would be as interested in philosophy, but after taking his class, I think he really puts a desire to know more and to see how you can apply these [essays] in your life, even if it’s not a philosophy you believe.”

Philosophy Professor Dawn Gale has a similar observation, noting whats alike about board games and philosophy.

“I think that all of those things incorporate philosophy into the stories and the process, and he incorporates all those things into the classroom,” Gale said. “In terms of gameplay … it all involves logical reasoning and critical thinking, which are the most important skills that we teach in a philosophy classroom.”

Whether it’s a comic book, philosophical essay, or Dungeons and Dragons, Conrad always loves a good story.

“The aesthetics and the story behind a game are very important to me,” Conrad said. “One thing I like about some philosophers, Nietzsche would be one, Plato would be one, Jean-Paul Sartre would be one, is I think their stories are really interesting. You can sort of see … [they’ve] got this philosophy, but there’s all these little stories inside of the philosophy. There’s the story of the allegory of the cave, which I think is really interesting to think through and has some great value.”

Conrad believes the work of philosophers can be applied even to issues they never discussed; in a like way, a game must be played within a set of rules.

“When you play a board game, you have a set of rules you’re dealing with,” Conrad said. “Then, you have to figure out, within those rules, ‘how can I succeed at whatever task this board game has set for me?’ You also, occasionally have to interpret rules when there seems to be a situation in the game where the rules don’t cover it or they’re unclear how they’re covering it. It seems like when you read many philosophers, there’s this question of ‘what do they mean?’ An interpretive question. If it’s a work in ethics, there’s a question of ‘how do I apply the ethics of this philosopher to this situation that, perhaps, they have never discussed?’ For example, I don’t know of a place where [Emmanuel] Kant clearly discusses abortion so you … have to figure it out based on things he does discuss elsewhere.”