Imagine living in a country for 23 years, from childhood to adulthood, without access to the benefits that other citizens take for granted. You can’t apply for a car loan, easily access any type of financial aid for school, or even travel outside of the U.S. without fear of being deported to the country in which you were born.

These challenges have plagued Alexís Villalpando-Padilla, a 27-year-old freshman at JCCC, for most of his life. In this article, Villalpando shares his experiences as a person in DACA – or, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals – program.

“I was 4-years-old when I moved here from Jalpa, Zacatecas, Mexico.” He said, “In 2008, when Obama was elected, my parents decided to [en]roll me into the program so I can get more of a legal status, rather than living in hiding.”

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) protects eligible immigrants who were brought to the United States as children from deportation according to a University of California Berkeley legal assistance page.

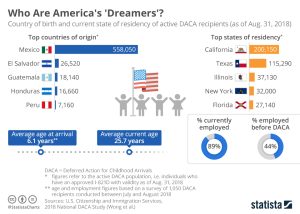

Image source: https://www.statista.com/chart/11072/who-are-americas-dreamers/

Image source: https://www.statista.com/chart/11072/who-are-americas-dreamers/

Villalpando’s immigrant status complicates other aspects of his life, as well.

“I’m not able to go back to Mexico. If I did want to go back, I would have to put in a request to leave. Then, I would have to get permission to leave, or else I’m permanently stuck in Mexico. Every two years I have to renew my status, and that’s around 800 dollars every year, just to renew it. Also, I have to renew my driver’s license and retake the test every two years.”

Despite its limitations, there are benefits to gaining DACA status.

Padilla says, “It has been an improvement rather than trying to live in hiding, and I can actually apply for jobs without having to do anything under the table.”

Still, negative stereotypes continue to impact his ability to buy a car.

“Every time I go to a dealership and I show them my work VISA, they don’t even give it a shot or try to give me something. Car dealership employees have actually asked me before, ‘Are you going to Mexico in the next three days?” Padilla continues, “Everything is perfectly fine until they get to know my status. So when it is time to finance a car, 4-plus hours, all with no luck.”

Changes in political opinion regarding DACA in the past six years have also impacted Padilla.

“I did pay more attention when Trump was in office, mainly because he was trying to get rid of DACA for the longest time,” Padilla said. “I wasn’t 100% scared myself since I had the protection of that status, but I was definitely scared he was going to take it away, then go through with that [deportation]. But, I was also afraid for my family. If they would do it to me, they would also definitely do it to my family, as well, and yeah, I was completely afraid”

Completing the paperwork for financial aid for school is also a struggle, but Villalpando maintains a positive mindset about it all.

“I don’t currently have any financial aid. But, for next semester, hopefully, I’ll be able to complete those things for financial aid.”

According to NBC News, 2.76 million immigrants from South and Central America have immigrated to the U.S since Jan. 2022. Nearly 130,000 are young children who will eventually enter the DACA program.

In closing, Villalpando offered advice for recent, young immigrants to the U.S.

“Don’t let fear consume you, and look for what options you have to actually reach that status, to reach full citizenship,” he said. “See if you can get any type of schooling, and don’t get stuck into a kitchen field that can sink you into a hole. Look for better options, rather than mainly being a common worker.”

Eliana Klathis, features editor